In 1940, the armies of the Wehrmacht occupied France and the rest of Europe, while the Luftwaffe and Admiral Denitz’s U-boats blockaded Britain and the northern seas. A year later, Germany controlled territory from the Arctic to Africa and from the Bay of Biscay to the Volga. It was supplied with raw materials and machinery by more than three hundred American companies, such as Ford Motor Company and General Motors, Aluminum Company of America, DuPont, IBM, International Telephone and Telegraph, etc. – many of which had invested heavily in Germany’s growing industry for years and were actively helping to arm it. Stalin also helped his friend and partner by sending Hitler trains of chromium and molybdenum, raw materials, and oil. The last grain train rattled off from east to west in the early hours of 22 June 1941, two hours before the German invasion.

War is possible as long as there is enough fuel in the tanks of tanks and airplanes and enough raw materials for the production of shells and ammunition. Having occupied vast territories, Germany was running out of everything. And Japan did a stupid thing attacking Pearl Harbour. And in December 1941, the war changed from a European war to a World War.

Field Marshal Paulus’ army, desperate to seize the oil of the Caspian Sea, was stopped at Stalingrad. In Egypt, Field Marshal Rommel’s Panzer Corps was on its way to the Suez Canal to seize Arab oil. If the Germans had seized the oil, the outcome of the war would have been different. The Americans and British launched the Battle of the Atlantic to put pressure on Italy to surrender. To occupy its ports and airfields and to draw Germany into the second front.

In 1942, Admiral Denitz’s submarines were the masters of the Mediterranean. Based in the southern ports of occupied France, they appeared everywhere, sank American and British transports, and were invulnerable to enemy aircraft. The secret of their invulnerability lay in the information they exchanged using a unique cipher machine called ‘Enigma’, the secrets of which the best minds in Britain struggled in vain to decipher.

In early May 1941, the British destroyer Bulldog captured a U-110 submarine in the waters of the North Atlantic. The prize was the very same Enigma, with a set of codes that the submarine commander had no time to destroy. The destroyer sank the boat, and this incident was reported in British newspapers to reassure the Germans that the Enigma had gone down with the boat. The decryption of the Germans’ secret correspondence helped the Royal Navy to capture 9 tankers at sea that were supplying fuel to Dönitz’s submarines. This immediately reduced the effectiveness of the operations, but the Germans suspected something was wrong and changed the codes. And their war plans again became a secret to the British.

In 1942, the Third Reich’s U-boats sank 1,661 American and British transports carrying 6.5 million tonnes of cargo. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill told the Royal War Council: “We are being ruined by Denitz’s U-boat fleet. Only victory over him will ensure our victory in the war…”.

CLEVER LIEUTENANT

Admiral John Godfrey was Director of the British Navy’s Directorate of Naval Intelligence. His assistant was a clever lieutenant. At the end of March 1942, a critical year for Britain, this lieutenant proposed to his boss the creation of a special unit of saboteurs, modeled on the German Abwehr-Commando “Brandenburg”. This secret foreign intelligence brigade proved its effectiveness in operations in Yugoslavia, Greece, and the USSR. The commander of the saboteurs was one von Hippel, and they reported only to the head of the Abwehr, Admiral Canaris.

In May 1941, during the operation to capture the island of Crete, the paratroopers were the “Brandenburg” parachute commandos. It was they who ensured the main success of the operation, capturing the British command posts and tons of secret enemy documents, allowing the Germans to quickly establish control of communications in the eastern Mediterranean and eliminate the threat of British aircraft bombing the oil fields of Romania.

But back to the Lieutenant. In his report to the Admiral, he explained the importance of creating a similar sabotage unit whose first target would be the secret codes of the German Enigma cipher machine. The Lieutenant’s proposal was immediately accepted and the 30 Assault Unit (30AU) Brigade was urgently manned.

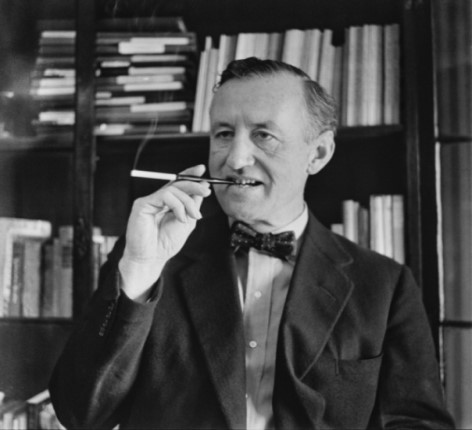

The unit’s personnel learned the science of blowing things up, killing, and kidnapping. The number ’30’ was the number of the office in the Admiralty in London where the group was headquartered. The Lieutenant Commander himself, who had been given command of the Brigade, called his boys “Redskins”, probably associating them with the fearless Indians of the Wild West. His name was Lieutenant Ian Fleming. The same one who, after the war, gave the world a series of novels about the fearless adventurer James Bond, Agent 007. Fleming chose himself as the prototype for the hero of his novels.

In late October 1942, the British HMS Petard attacked a German U-boat off the coast of Egypt. An officer and two sailors risked their lives to swim to the stricken boat to retrieve the secret codes of its cipher machine. Two of them were dragged to the bottom by the boat, but one was lucky, a sixteen-year-old young man. He delivered the documents to the ship. This trophy again helped Britain and America, but soon the Germans suspected something was wrong and mathematicians built them a new cipher machine, the world’s first digital computer. Fleming’s Redskins hunted this machine for the rest of the war. They also had plenty of other targets.

On the night of 21 April 1943, at the Battle of Medjeb el Bab in Tunisia, the British managed to put the new German Tiger tank out of action. This tank had been developed under the personal supervision of Hitler and was a formidable weapon. The British tried to drag the 56-tonne tank carcass off the battlefield, but the Germans resisted all attempts. Fleming’s brigade found itself in the battle zone and, after surrounding the Germans with their agile jeeps armed with anti-aircraft machine guns, forced them to retreat. The “Tiger” proved to be a valuable trophy.

Fleming was also involved in the planning of several major operations. In May 1941, he accompanied his boss, Admiral John Godfrey, to America, where he helped set up the Secret Service that would become known as the CIA after the war. Fleming was also involved in devising an operation to maintain the intelligence structure in Spain in the event of a German takeover. His brigade was successful during the war.

Fleming’s boys were particularly successful in 1944 during an offensive on the port city of Kiel, home to a German research center developing engines for the Fau-2 ballistic missile, the Messerschmitt Me-163 jet, and high-speed submarines. After the operation, Hitler ordered that captured saboteurs from the 30th Attack Squadron be shot on sight. So Fleming was no ordinary lieutenant, a competent enough scout to create his Bond.

CARIBBEAN.

After the war, Ian Fleming became foreign director of a major newspaper, overseeing the publication’s worldwide network of correspondents. He bought a house in Jamaica, where he spent his holidays writing James Bond novels. The first novel in the future series was Casino Royale. After reading a draft of the novel, his friend and writer William Plomer wryly remarked that “…any element of intrigue is missing, completely…”. Nevertheless, he encouraged his friend, saying that the book might well interest the reader, and sent the manuscript to the publisher he was working with.

There, too, the novel was initially received with little enthusiasm, and in April 1953 Casino Royale was published in hardback at the modest price of 10 shillings and 6 pence. The book sold out quickly and readers’ demand was met by three extra printings. Thus life proved to the publishers that the opinion of the literary critics was far from being the final truth.

In 1962, in an interview with journalists from the weekly magazine The New Yorker, Fleming said: “When I wrote the first novel, I wanted Bond to be a simple, unremarkable man, but something happened to him; I wanted him to be a tool in the hands of politicians, to begin to show initiative… When I was struggling to find a name for the main character, I thought James Bond was the most boring name I had ever heard.

The image of the protagonist of all his novels embodied the qualities of the people Fleming worked with in the secret service. The author realized that Bond combined all the types of secret agents and commandos he had met during the war.

After the publication of the first novel, Ian Fleming used every regular holiday to fly to Jamaica, where he wrote his “Bondiad”. All 12 Bond novels and two collections of short stories were written between 1953 and 1964. Much of the source material for the novels came from his own experiences in naval intelligence and from the events of the Cold War. The first five Bond books – “Casino Royale”, “Live and Let Die”, “Moonraker”, “Diamonds Are Forever” and “From Russia With Love? – were generally well received. However, critics and envious detractors described Fleming’s work as “writing without any ethical guidelines”.

Coincidence helped. In 1961, at the height of its critical acclaim, Life magazine named “From Russia With Love” as one of President Kennedy’s ten favorite books. The news spread nationwide, boosting sales and making Fleming the most popular crime writer. Fleming himself considered “From Russia With Love” to be his best work.

In April 1961, at the weekly meeting in the Sunday Times newsroom, he suffered a heart attack. The strain of life had taken its toll. Two months later, Ian Fleming sold the screen rights to published and future James Bond novels and stories to Hollywood producers. The film company “EON Productions” was formed to produce five films starring Sean O Connery.

The image of Bond portrayed by O Connery in the films influenced Fleming: in the novel “You Only Live Twice”, the actor gave Bond a sense of humor that was lacking in the author’s books. In January 1964, the author spent his last holiday in Jamaica, where he wrote the next novel in the series, “The Man with the Golden Gun”.

An avid smoker and alcohol addict, Ian Fleming lived a life of exhaustion. On 11 August 1964, he was in a Canterbury hotel on his way to lunch at the golf club. The day proved to be an exhausting one for him. He died early the next morning. The 56-year-old’s writer’s last words were an apology to the paramedics: “Sorry to bother you. I don’t know how you manage to drive so fast on the roads these days”.

Ian Fleming was buried in a churchyard in the village of Sevenhampton in his native England. The family struggled to come to terms with the tragedy, especially his eight-year-old son Caspar. In October 1975, at the age of 23, he killed himself with an excessive dose of drugs.

ABOUT HIS WRITING STYLE.

Fellow writers have noted that Fleming’s work can be divided stylistically into two periods. The first includes works written between 1953 and 1960, in which the author concentrated on “the mood and character of the plot development”. The works from 1961 to 1964 were more detailed and imaginative. In them, the author became a “master storyteller”. Fleming himself said humorously of his work: “…although the thriller cannot be called literature with a capital letter, it is fair to say that my thriller is intended to be read as literature”.

In May 1963, Fleming wrote an article for a magazine describing his approach to writing Bond stories: “I write for three hours in the morning… and work another hour or two between six and seven in the evening. I never correct anything or go back to see what I’ve written… just follow my formula of writing two thousand words a day”.

Fleming’s style is called the “Fleming sweep”, or the hook the author throws in at the end of a chapter to draw the reader into a new chapter. Perhaps it is this technique that has made his books a fascinating read for millions.

Thirty million copies of Fleming’s books were sold during his lifetime; twice as many in the two years after his death. In 2008, The Times ranked Ian Fleming fourteenth in its list of the “Fifty Greatest British Writers Since 1945”. EON Productions continued to make Bond films after the author’s death. Twenty-four adaptations have grossed over $6.2 billion at the worldwide box office, making the Bond franchise one of the highest-grossing film franchises of all time. An international airport in Jamaica was named in honor of Ian Fleming and opened in 2011.

The twentieth century has given mankind many writers. Among them are three whose novels are still loved and read by people all over the world: Remarque, Hemingway, and Fleming.

Three names – one destiny! War, addiction, the love of a woman, personal drama. It must have been a hellish mixture of all these things that ignited their talent. They flew across the sky like burning comets, setting many hearts on fire themselves. Death in flight, in the prime of life!

They were so similar to each other, among hundreds of millions of others, that one can’t help but wonder – from which world they were, from which galaxy…? Perhaps the jealous gods also wanted to read novels, so they took them for themselves.

The writers of the lost generation. A generation that had lived through the horrors of two world wars and saw the world differently to those who were not in the trenches. They wrote about what they saw in their books.

© Copyright: Walter Maria, #217111001654

Very interesting info! Perfect, just what I was searching for!

Thank you for your sharing. I was worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you.