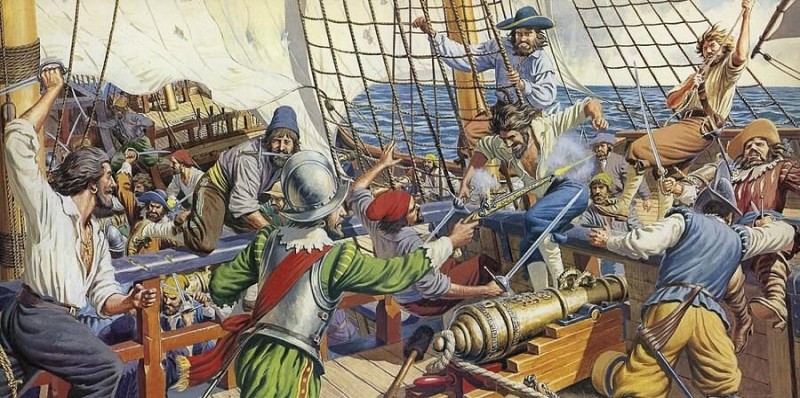

Piracy dates back to ancient times, when people first started using sails on boats. These sea robbers were known as pirates and criminals. However, in the Middle Ages, some monarchs began to employ them. In 1243, for example, King Henry III of England granted his sailors licenses to operate as privateers and seize enemy vessels. This guaranteed the privateers protection from the gallows in exchange for a share of the spoils. During the conquest of the New World, all European monarchs resorted to this kind of partnership. They needed a fleet at home to defend their European territories. So they hired captains and granted them licenses to plunder in the New World. One of the most famous English privateers was Francis Drake, who was knighted and appointed admiral by Queen Elizabeth I in recognition of his exploits. However, when the warring parties made peace, the privateers lost their licenses. Accustomed to easy money, some of them continued to plunder illegally. In other words, they were becoming pirates. The king, who had previously granted his vassal a license to plunder, was now branding him a criminal and ordering his execution.

Pirates were adventurers, and men of fortune valued freedom. No monarchy guaranteed that. Therefore, many were tempted by the forbidden fruit and joined the pirate trade. Soon the monarchs realized that piracy was a growing threat to their crown. Eventually all the kings put aside their differences and declared war on the pirates. But could cannons stop the wind?

Modern writers and historians tend to portray the pirates of this period with sarcasm, seeing them as despicable criminals. Perhaps this is due to the well-established view that all pirates were thieves and criminals. There was certainly some truth in that. However, there was another side of the coin. In the waters of the New World, some pirates were educated sailors and officers from wealthy families, even gentlemen. They had reputations in society, large estates and lots of money in the bank. So why did they throw themselves into adventures, risking their lives, choosing danger and hardship? This story is about such people.

***

CHEVALIER.

Michel de Grammont’s sixteen-year career was so eventful that his exploits in the New World achieved legendary status. Born in Paris, he was the son of a royal guard officer. Following his father’s death, his mother remarried. His beautiful sister was courted by a guard officer who frequently visited their home. Young Michel watched his sister’s affair with jealous eyes and once advised her admirer to visit less often. When a scandal erupted, the officer became furious and insulted de Grammont.

‘If I were older, my sword would teach you a lesson,’ the young man replied. The affair ended in a duel, which de Grammont won mortally wounded his insulter. In those days, honor was more valuable than gold, and the dying man left part of his fortune to de Grammont in his will. He also admitted that it was his fault and asked that the young man not be punished.

Upon learning of this incident, King Louis XIV ordered the duelist to be sent to a naval cadet school. There, the young Gascon learnt the science of naval navigation and gained a reputation as an excellent fighter and brawler. In the West Indies de Grammont served as a junior officer on a French warship. Skirmishes and the capture of enemy ships were commonplace, and after surviving several such events, the ambitious de Grammont wanted to take on a leadership role.

Taking advantage of borrowed funds, he outfitted an old frigate and set sail, capturing a Dutch merchant ship laden with treasure. He generously divided the booty with the crew, keeping 80,000 francs in silver for himself. This quickly acquired wealth turned the head of the young man. De Grammont spent the money on expensive clothes, parties and gambling. However, his command decided that such behaviour was unworthy of a royal officer. De Grammont was dismissed.

But the young pirate’s adventures had only just begun. They continued on the island of Martinique, where he soon obtained a privateer’s license from the local authorities and became the captain of his own ship. How the disgraced officer came to be among the buccaneers — the first pirates of the Caribbean — remains a mystery. Among his new comrades, the vain de Grammont insisted on being called ‘Chevalier’, a nickname that would soon become recognizable along the coasts of all the Caribbean colonies.

THE RAID ON MARACAIBO.

Meanwhile, the struggle for overseas territories continued in Europe. In 1678, war broke out between France and the Netherlands. In the New World, the French planned a joint naval attack on the Dutch colony of Curaçao. The expedition was led by Admiral d’Estre. De Grammont commanded an army of 1,200 buccaneers from Tortuga and Saint-Domingue (now Haiti).

However, en route to Curaçao, a storm drove several ships from the squadron onto the reefs of Bird Island. The expedition was a failure, and d’Estre sailed back to Martinique with the remains of the fleet. De Grammont, however, decided to plunder the Spanish settlements in the Maracaibo Lagoon instead. The 6 ships fleet and 700 brigands were with him.

They attacked the Spanish fort that guarded the entrance to the lagoon and seized it. However, the settlements were empty. Pirates Olone and Morgan, the leader of the buccaneers, had already looted the area. De Grammont left part of the fleet at the lagoon entrance and sailed three ships south to the town of Trujillo, located ten miles inland. En route, the pirates captured a village whose inhabitants fled in terror.

“Captain, we have a hundred horses and now have meat,” reported the chief of the detachment.

‘We have no meat yet,’ replied Chevalier, staring at him without blinking. ‘Where are you from?’

‘I grew up in Jamaica,‘ the pirate replied proudly.

“I see you are not from Paris,” said Chevalier, smiling as he lit his cigar. ‘And what other wild animals have you encountered besides boars?’

‘The Spaniards, captain! Spaniards!’ – laughed the pirate.

‘These horses must not be touched!‘ De Grammont became serious. ‘Gather everyone who can ride. These horses will help us take the city! The Spaniards are no fools if they could find and conquer these lands. They’re just not trained to fight,‘ he said, puffing on his cigar.

Trujillo was defended by 350 soldiers and a battery of 30 cannons. Pirate cavalry attacked the town in small groups from behind, causing panic among residents. The pirates returned to their ships with rich booty.

By transferring his men onto captured horses, de Grammont created a new type of army, the flying cavalry. Soon such units would appear in the armies of all European powers.

In 1680, de Grammont travelled with 180 pirates to the coast of Cumana. There they attacked Puerto Cavallo, capturing and destroying two forts and seizing all the cannons. They were opposed by an army of two thousand Spanish soldiers and natives. During the battle, de Grammont was severely wounded in the neck, after which the pirates carried off their wounded captain. The pirates fought with such ferocity that the Spanish were forced to retreat. They took 150 prisoners, including the governor of the town, and left the harbor in their ships. While waiting for ransom, they were caught in a hurricane off the coast of Goaiva, their ships were wrecked, the wreckage washed ashore. Among them was the 52-gun flagship that held all of de Grammont’s wealth.

It took Chevalier a long time to recover from his injury. He became quite impoverished. One day, however, his old friend Nicholas van Hoorn visited him and suggested that they should raid a Spanish colony rich in gold. He added that the gold would solve all of Chevalier’s financial problems. De Grammont found the offer so tempting that he expressed his desire to join the expedition as a sailor. He no longer had a fleet.

“My friend,” replied Van Hoorn, “everyone here knows that you are a brave man and an experienced sailor. In addition to all your virtues, you are a nobleman and honour means a great deal to you. I appreciate your qualities and your bravery. I offer you a frigate with three hundred men at your disposal.’

Nicholas Van Hoorn smiled as he puffed on a cigar.

The Mexican port city of Veracruz lay at the heart of his plans. Founded by the conquistador Hernán Cortés, it was a secure fortress equipped with 60 cannons and defended by a garrison of 3,000 men. The nearest ports also had garrisons totalling 15,000 men. Although Veracruz was a promising target, they didn’t have enough men for such a dangerous mission. They needed one more partner.

NICHOLAS VAN HOORN.

He was a Dutchman who had started his career in maritime robbery in the Netherlands. He had a fishing license, owned a fishing boat with three dozen armed thugs. They robbed their compatriots as well, which eventually brought them into conflict with the authorities. Before fleeing to France, Van Hoorn bought a load of weapons in Ostende. There he was helped by relatives of his French wife, mademoiselle Leroux. Her father was an agent of the West India Company, and it was probably through his patronage that Van Hoorn was appointed chief commissioner for receiving cargoes in the Spanish port of La Coruña, and was in service of the French king. Looking at the untold treasures delivered from the New World, Van Hoorn remembered his pirate life and applied for a privateer’s license. He crossed the ocean and within a few years had amassed a small fleet. His adventures soon became well known to many.

One day, his audacity nearly proved fatal. Van Hoorn had attacked a French merchant ship. When news of this reached Versailles, the governor of the overseas colony was ordered to arrest the privateer. Admiral d’Estre sent a warship after Van Hoorn. Realizing how things might end for him, Van Hoorn made an attempt to resolve the situation. With a dozen loyal crew members he came on board of warship and made up a story about some of his crew who had supposedly escaped on that French ship. He therefore tried to retrieve them by force. However, the French did not believe him and were intending to take him into custody.

Van Hoorn was furious.

‘Are you going to do this?’ Do you think my men will allow you to take me away from them? You should know that they are quick and obey my orders without question. They have faced worse dangers and are not afraid of death!’

The determined expressions on the guests’ faces made it clear to the commander that their leader was serious. He had orders to arrest the privateer, but not to endanger the lives of the king’s men. For political reasons above all else, he therefore decided to let Van Hoorn go.

One day, Van Hoorn learned that a convoy of Spanish galleons was waiting in Puerto Rico for a military escort to accompany them on their journey. As he held a privateer’s license from the French governor that permitted him to attack Spanish ships legally, he seized his opportunity. He travelled to Puerto Rico and offered the governor the use of his fleet to escort the caravan across the Atlantic to Spain. The naïve Spaniards agreed. Once on the high seas, Van Hoorn plundered and sank several galleons, taking the most valuable cargoes — gold, jewelry, and precious stones.

During the boarding fights, he killed any of his own crew who showed signs of fear or cowardice. The crew both feared and respected their captain. They knew they would die for their transgressions. But they also knew that if the operation was successful, the captain would share his wealth. This fierceness of temperament, coupled with a peculiar coquetry, was a defining feature of Van Hoorn. He wore luxurious clothing and adorned himself with a string of large oriental pearls around his neck and a ring bearing a large ruby on his finger.

LAWRENCE DE GRAAF.

Lawrence de Graaf was a Dutchman who always seemed to get his own way. An artillery expert, he initially served the Spanish, fighting against pirates. After being captured and sold into slavery, he escaped and became a pirate in the New World. He lived among the buccaneers and married the renowned hunter Pierre Long’s widow, who was the founder of Port-au-Prince in Santo Domingo. De Graaf’s experience and bravery soon made him a terror to the Spanish.

One day, his small ship was pursued by two Spanish galleons, each armed with sixty guns. One was an admiral’s flagship, while the other was commanded by a vice-admiral. The galleons had 1,500 men on board and were firing all their guns. Outnumbered, the pirates were threatened with boarding from both sides by the Spaniards. Many of the pirates thought their end was near.

However, de Graaf convinced his crew that they would all face a shameful and agonizing death if they were captured. His words inspired the crew to fight to the death.

He ordered one of his bravest pirates to stand by the open hatch of the powder chamber with a burning fuse, waiting for the signal that would be given when all hope was lost. Meanwhile, his skilled buccaneers fired their muskets, killing dozens of Spaniards crowded on the decks of the enemy ships in preparation for boarding.

De Graaf was wounded in the thigh, but still managed to utilize all his artillery skills. His cannonball broke the main mast of a Spanish ship, causing panic among the enemy.

Seeing their opportunity, the pirates broke free and sailed away with the wind at their backs. Once again, luck was on de Graaf’s side!

Madrid was so furious at this disgrace, that the captain of the warship who had dishonored its flag was beheaded. De Graaf gained fame and notoriety.

A year later, while searching for a prize, he prowled the waters off Cartagena. There, his two ships were attacked by three Spanish warships. The pirates proved to be more determined and captured all three Spanish ships. De Graaf had a sense of humour and sent a letter to the governor of Cartagena thanking him for this generous Christmas gift. The whole pirate world laughed, and de Graaf’s victory fuelled the ambitions of his crewmates. Van Hoorn and de Grammont invited De Graaf to take part in the attack on Veracruz.

De Graaf at first refused their offer. Despite his fondness for such ventures, he felt that a raid on Veracruz might not be successful. He preferred to plunder Spanish ships at sea rather than get involved in a land war. However, Nicholas van Hoorn did not want to lose such a valuable ally, so he reminded de Graaf of de Grammont’s successful raids on Spanish settlements. Moreover, van Hoorn had royal authorisation to plunder Spanish ships and settlements. He added that such opportunities were unlikely to arise again in the foreseeable future. This dispelled de Graaf’s doubts about the success of the forthcoming mission, and he finally agreed.

After assessing all the risks, the three hotheads started thinking about how they could carry out their plan. Van Hoorn had just received some valuable information: two merchant ships loaded with cocoa were about to arrive in Veracruz. Trinity planned to take advantage of this by disguising their own ships as the merchant vessels.

VERACRUZ

Veracruz was a fortress, its fortifications could withstand the attack of an entire army. But that didn’t deter the trio. They knew that cunning and determination could work wonders. They had a fleet of a dozen ships and an army of a thousand three hundred sabers and muskets. It was an impressive force for the time, the largest since Morgan’s raid on Panama in 1671.

But even with such a force, attacking Veracruz, surrounded by garrisons of 15,000 Spanish soldiers, was madness. But night was a pirate’s best friend! The Spanish always ended up on the losing side because they didn’t take pirates seriously, relying on their soldiers.

When they saw the long-awaited Spanish-flagged ships, all the people of Veracruz, young and old, rushed to the port, rejoicing that they would now have cocoa, their favorite chocolate drink.

The people’s joy was replaced by surprise when they noticed that the ships were keeping their distance and not entering the harbor. Suspicion gripped many and they reported the matter to the governor, Don de Cordova. But the governor assured them that they were the very ships reported to him and that they matched the description. The commandant of the fort received the same answer but advised the governor to be cautious. Night fell upon the town, and the people dispersed to their homes.

In the pitch darkness of the southern night, the remaining ships of the pirates came from behind the horizon and joined their three ships. The fleet headed for shore and the pirates landed on an unguarded promontory near the old town. They immediately captured and killed the sentries on shore, and in exchange for his life, one agreed to be a guide and led the pirates to the unguarded city gates. The pirates entered the city and the massacre began.

De Graaf led his detachment to the fortress that protected the town from attack from the sea, and they took it. Here the pirates turned around the twelve cannons that had been set up to protect the town from the pirate ships. Now the pirates fired these cannons at the buildings of the town, direct fire.

The Spanish soldiers, awakened by the sound of explosions, smoke, and flames, could not think straight. The next day was a Catholic feast day and many soldiers thought that some of the citizens had thought of starting the feast early. Even the screams of the pirates’ victims they heard were taken as a sign of joy. In short, the defenders of the city were the last to know that there was nothing left to defend, the city was already in the hands of the filibusters.

Finally, the soldiers, realizing what was happening, began to shout with all their might that “las drones” (thieves, robbers) were in the city. Enraged by the soldiers’ resistance, the pirates killed everyone they could get their hands on. By dawn, all the soldiers had been killed, some had fled, and the city’s officials and rich men had been captured.

The prisoners were locked in the cathedral and all entrances were barricaded with barrels of gunpowder. Guards were posted with lighted fuses, ready to blow up the church and everyone inside at the slightest attempt to escape.

All day and into the next night they plundered and carried the loot to their ships. A cursory count put the booty at 6 million in gold, silver, coins, and gems. Time was running out, and the pirates feared that troops stationed nearby were about to descend upon them. They rushed the prisoners to their ships, expecting to get for their souls as much, if not more than they had already taken.

When it came to counting and dividing the booty, the two companions, van Hoorn and de Graaf, disagreed. They also disagreed on the method of collecting the ransom.

Van Hoorn wanted to burn the merchant ships in the harbor and execute some of the captives, claiming that this would intimidate the Spaniards and speed up ransom payments.

De Graaf disagreed, insisting that it would be wiser not to wait for the Spanish troops and their ships, but to leave with booty and prisoners that could be ransomed later through diplomacy. The contending parties were not averse to verbal abuse, and the matter ended in a duel.

De Grammont shared Lawrence’s opinion but did not interfere in the dispute between the two Dutchmen.

The duel took place on a neighboring island on the twenty-ninth of May 1683. According to the terms of the duel, the winner would be the first to shed his opponent’s blood. De Graaf was lucky in this duel. The wounded van Hoorn was confined to the bed in his quarters. The pirates received their ransom and left.

Nicholas van Hoorn died of an infected wound and was buried on the small island of Loggerhead Cayo. This was the end of one of the cruelest and most cunning pirates.

Meanwhile, the French King tried to end the destructive feud and make peace with the Spanish Kingdom. Peace was declared, but French privateers and pirates were aided and abetted by the Spanish themselves. Despite the truce, they continued to seize French ships.

The governor of Martinique, de Cussy, who respected de Grammont’s courage and ability, presented his candidacy to the French government in the most plausible light, suggesting that the privateer be appointed governor of the southern part of the island of San Domingo. Paris agreed, and de Grammont was flattered by the confidence shown in him. But he decided to celebrate the end of his pirate career with one last raid into the Gulf of Mexico. As a gambler, he wanted to end the game with an ace of trumps!

CAMPECHE.

In early 1686, the leaders of all the buccaneers and pirates gathered on Cow Island, southwest of Española, for a council. Chevalier proposed a raid on Campeche, a Mexican port on the Gulf Coast. His comrades, remembering the last raid on Veracruz, expressed doubts, arguing that the venture would risk death. No one wanted to die. The Spaniards hanged captured pirates without trial. But the privateers were vassals of their king, and politics was involved, so they were sent to prison. From there was a chance of returning to a prisoner exchange or simply escaping.

De Grammont appealed to Governor de Cussy for a privateer’s charter. But in Europe, the monarchs had already negotiated an armistice. So de Cussy refused the Chevalier’s request and sent him a letter informing him that the French government forbade all attacks on the Spanish and would soon send warships to force all pirates to obey.

This news hit the pirates like a red rag on a bull and gave de Grammont a better chance of success. He was persistent, and in another letter to the governor, he repeated the request, alluding to the fact that the king did not know the true situation in the colonies. But the governor could not disobey his sovereign. Still aware of de Grammont’s influence among the buccaneers, the official promised him, on behalf of the government, a special reward if he would renounce his brotherhood with the pirates forever and return to public service.

To which de Grammont replied: “There are no traitors in our brotherhood. If my comrades-in-arms agree to renounce their intentions, I am prepared to do the same.”

Tired of this diplomacy, the pirate leaders declared that if the governor would not grant them a privateer’s charter, they would dispense with the paper, for their goal remained the same: to capture the beasts that defied them. One thousand two hundred cutthroats saluted with their sabers.

On 5 July 1686, their ships were fifteen miles from Campeche. Here the 900 fighters jumped into the boats and worked the oars. In the rainy twilight, they approached the shore. There a few hundred unsuspecting guards warmed themselves by the fires. The pirates sneaked up and attacked them, hacking many to pieces.

They then infiltrated the town, where the church bell had already caused panic. The fort garrison began firing cannons at the attackers, but de Grammont ordered his best marksmen to kill anyone who approached the cannons. The cannons fell silent.

After taking the fortress, the pirates aimed the cannons at the city. After the first shells blew the walls of the houses to pieces, the town capitulated. Armed with sabers and muskets, the pirates in a few hours took the city, fortified according to all the rules of military art, with a large garrison, cannons, and fortifications.

Among the prisoners was an Englishman who had served with the Spaniards as an artilleryman. The young officer preferred to die rather than flee the battle. De Grammont was surprised by the nobility of the prisoner and released him.

While the pirates were plundering Campeche, help arrived from a neighboring town. An army of 800 men was led by the governor himself. Some of the pirates were ambushed, losing two dozen killed, and a few were captured by the Spaniards.

De Grammont began negotiations, offering to release all captured officials and wealthy townspeople in exchange for the prisoners. He added that if the commander of the army refused such a generous exchange, he would order all the prisoners to be chopped to pieces and the city burnt.

The governor commanding the army replied haughtily:

“The pirates are free to burn and kill. We have enough money to rebuild the city, and enough troops to destroy you all, which is the main purpose of my campaign…”

Enraged at such boasting, de Grammont led the governor’s envoy through the streets of the city, ordered several houses to be set on fire, and executed five Spaniards before his eyes.

“Go to your master and tell him that I have begun to carry out his orders and will do so with all the other prisoners,” he said, smiling.

The governor did not risk bringing his army into the city. The Spaniards were gone.

For two months the pirates drank and debauched themselves, waiting for a ransom. God only knows how many French-blooded children were born after that. The women know, of course. But they always keep quiet about their sins. Not getting what they wanted, the pirates burned the town and returned to Tortuga. De Grammont didn’t kill the prisoners, he let them go.

His friend Lawrence de Graaf also took part in that raid. On the way back, their two ships separated, and de Graaf’s ship was chased by two Spanish warships. The day passed under fire exchange, and at night the pirate managed to elude his pursuers. The lucky man de Graaf was so damn lucky again!

Later, finishing with piracy, de Graaf pursued a career in politics, becoming a government official and helping to organize French Louisiana in America in 1699. Unlike most pirates, Lawrence de Graff died peacefully, surrounded by his family. He left them a considerable fortune, including a sugar factory and over 120 slaves.

And his friend’s ship was caught in a hurricane in Florida waters, killing all 180 souls on board. No one ever heard of the pirate nicknamed “Chevalier” again.

What is there to add…? Don’t sit down to play cards with Destiny, no matter how high your ace is…

© Copyright: Walter Maria, 2023 Certificate of Publication No. 223021802023

Be First to Comment