From the author.

Otto Skorzeny, nicknamed “Long Otto” because of his two-meter height, was a legend of the Third Reich and a special commando who carried out Hitler’s secret operations in many parts of the world. The methods of secret warfare used by the Abwehr’s special units are still being studied by the secret services of the United States, Israel, and Russia, and I am sure my readers will be interested to learn about them. I am offering here a story of Otto Skorzeny from his diaries where he tells of the most sensational operation, the kidnapping of the Italian Fascist leader Benito Mussolini. My publication also uses fragments from memoirs of those who took part in his operations or knew him personally.

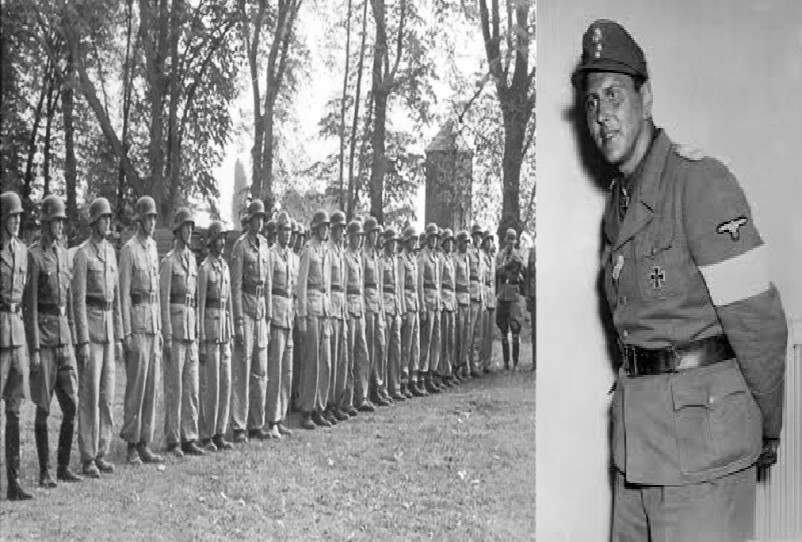

In April 1943, SS Hauptsturmführer Otto Skorzeny received orders to come to Berlin, to the headquarters of the Abwehr. His old friend Ernst Kaltenbrunner, now one of the Reich’s top officials, remembered Skorzeny, whose participation in the 1934 coup in Vienna had impressed him at the time.

In the office of Chief of Intelligence Schellenberg, Skorzeny was informed that he had been appointed Chief of Section VI of the SD’s Sabotage Service, head of the Friedenthal Group, to carry out reconnaissance and sabotage operations behind enemy lines. Skorzeny accepted the offer but asked to remain subordinate to the SS. He received his first order.

It was the “Ulm” plan, designed to destroy the industrial complex of the Urals. The planners of the General Staff Division believed that there was an oil pipeline connecting the oil fields of Kazakhstan with the industrial Urals. Skorzeny’s special team was tasked with destroying the pipeline to stop the oil supply to the Urals. Skorzeny was an engineer, and his actions were always preceded by calculations to avoid surprises. In an adventure, he refused to take unnecessary risks. It was this methodology that later made him a successful saboteur.

Skorzeny began by gathering as much information as possible from the Abwehr and the Gestapo, as well as studying aerial photographs taken by the Luftwaffe. All the information he received indicated that the pipeline did not exist.

In Kazakh, ‘shaitan’ means ‘devil’, and ‘Arba’ means ‘cart’. Shaitan-Arba means steam locomotive. This Soviet ‘Shaitan-Arba’ pulled a dozen tank cars with oil along the rails, and there were many such branches from the oil regions of Kazakhstan to the Urals, which made sabotage impossible. And small cargoes were transported by donkeys, as it was in the Middle Ages.

German headquarters, planning to defeat the sizeless Russia, thought by the standards of industrial Europe, but in those years Soviet Russia had not yet mastered the technology of laying oil pipelines. The donkey and the shaitan-arba turned out to be secret weapons of the Russians, unknown to Hitler’s generals.

When Skorzeny was preparing a memo to his superiors on the Ulm project, friends advised him to hide it away so as not to make enemies among the arrogant officials of the General Staff. The note safely disappeared into the archives. But rumors of the clever saboteur reached the Führer’s ears. And one day Skorzeny was summoned to the Führer’s field headquarters.

LIVING DANGEROUSLY!

In January 1943, the Anglo-American Allies held a conference in Casablanca. They issued an ultimatum to Germany, Italy, and Japan, demanding complete and unconditional surrender. For the Nazis, this meant the collapse of the Third Reich, the destruction of Germany’s military and economic potential, servitude to the world’s bankers, and life on their knees.

On 25 July 1943, Italy’s top officials, frightened by an order from Casablanca, arrested Mussolini during his visit to the royal palace. The new government of Prime Minister Badoglio was considering surrendering by handing over all the country’s Adriatic and Mediterranean ports to the Americans. And Mussolini’s was to be a trophy gift to the Americans.

For Hitler, Mussolini was an associate, a partner in the Anti-Comintern Pact. However, the Duce had cultivated a cult of personality, puffed up his cheeks on the podium, and generally revealed himself to be a poor politician and worthless military leader by the start of the Great War. As Hitler’s aide, SS Major Linge wrote in his memoirs, the Führer spoke of Mussolini with great sarcasm, saying that if Mussolini had not flirted with Churchill in 1939 but had declared his willingness to side with Germany in the Polish conflict, England and France would have refrained from declaring war.

In June 1940, when German divisions invaded France from the north and occupied Paris, Mussolini finally declared war on England and France. But he did nothing. Asked why the Italians were not attacking, Hitler received a laconic reply from Rome that it was raining in the border strip… As a result of the Italians’ inaction, British warships safely left the ports of southern France.

“If you give him confidential information, the whole world will know about it tomorrow. He is too Italian to be a military man,” the Führer laughed.

Now that Mussolini had been arrested, the German leader realized that the Duce had to be dragged out to save the Fascist regime in Italy, to stop the defeatist plans of the new cabinet, and to prevent the threat of a southern front.

The very next day after Mussolini’s arrest, 26 July 1943, Skorzeny was summoned urgently to Hitler’s headquarters. In a confidential conversation, he was instructed to kidnap Mussolini and bring him to Germany. Hitler informed Skorzeny of his responsibility to keep the mission strictly secret, adding that it would not be known to the military commanders in Italy. Air Marshal Kurt Student was assigned to command a group of Special Forces to take and hold Rome in the event of a betrayal by the cabinet of the new Prime Minister, Badoglio. Skorzeny and his team were under the General’s command.

He had an evening to himself. Late into the night, the teletypewriters at headquarters sent secret information to Berlin. He ordered his deputy, Obersturmführer Radl, to select 50 of the best saboteurs with a good knowledge of Italian and to complete the squad with equipment, weapons, and a week’s supply of food. Early in the morning, Skorzeny and a group of officers took an official flight to Rome. He thought about his mission. It was necessary to find Mussolini and get him out without casualties that might cause a stir in the world press and provoke politicians to accuse Germany of more murders. The Führer warned Skorzeny of the sensitivity of the mission. He pointed out directly that if the operation failed, it would be presented to the world as the act of a lone madman. As he left the office, Skorzeny recalled Hess’s escape to England. Hitler had then abandoned his closest associate, whose attempt to secure an armistice with England had failed. Hess ended up in an English prison. Reflecting on all this, Skorzeny realized that he either had to complete the mission or disappear.

OPERATION EICHE.

Five and a half hours later, the plane landed in the Italian capital. Skorzeny’s paratroopers arrived the next day and were housed in army barracks in the northern part of the city. Skorzeny was introduced to Himmler’s confidant, the commander of the secret police in Rome, and received full support for his mission. He managed to obtain information about Mussolini’s arrest during an audience at the Royal Palace, from where the Duce was taken away in an ambulance. All other traces of his stay were erased. Another fortnight passed in vain when news arrived from an unexpected source.

A fruit seller, sipping a beer at the bar, blabbed that his best customer, the restaurant owner, was lamenting the loss of contact with his lover. His homosexual partner was a carabinieri in the security service, and he told the lover that he couldn’t make an appointment because his group had been assigned to guard a “very important bird” on the island of Ponza, and all departures from the mainland were closed. Having received this information from the informant, Skorzeny guessed which ‘bird’ he was referring to.

Following the trail, he managed to get further information from a young naval officer who confirmed that Mussolini had been taken by ship to the island prison. Orders came from field quarters to attack the island within 24 hours. The next day, however, agents informed Skorzeny that the prisoner had been moved to another location and that additional secrecy had been imposed on the northern part of the island of Sardinia.

And then Skorzeny came up with a stratagem. Knowing that Italians are talkative, he ordered his Untersturmführer Varger, who was fluent in the local dialects, to disguise himself as a soldier and play a game in a local pub.

Varger was in a pub, drinking beer and listening with his ears wide open. As soon as he caught a glimpse of the right phrase, he made a bet with the drunkards that Mussolini had already died of an illness. Another fruit seller had fallen for his money! Apparently, in Italy, banana sellers know state secrets better than the secret service. This one swore that he had seen Mussolini alive and well at Villa Kern yesterday, and offered to show the living Duce to prove it. For money, of course. The villa was on the outskirts of town, and the greengrocer took Varger along secret paths to see the veranda of the living object with his own eyes. The merchant got his money, but he didn’t have time to spend it. He was too talkative for the big game, so he went to feed fish. It was 17 August 1943.

It was possible to attack the villa, but the pre-war map of Sardinia was out of date. In recent years, new channels had been dug on the approaches to the island and coastal defenses had been built. The operation was to involve a minesweeper, so the latest photographs were needed to determine all the details of the forthcoming operation with maximum accuracy. General Student gave Skorzeny everything he asked for and early the next morning the Heinkel-111 took off. In addition to Skorzeny, there were two pilots and two machine gunners on board. The plane climbed to an altitude of five kilometers and Skorzeny had time to take photographs when they were suddenly attacked by two British fighters.

One of the engines failed, a hole was created in the fuselage, and the airplane was rapidly losing altitude. The pilots held the plane from going into a dive as best they could.

“We fell into the water, and the impact was so strong that I lost consciousness,” Skorzeny recalls”, “I woke up to one of the pilots pulling me out of the water by the neck and shaking me as hard as he could. I was gulping air with my mouth like a fish. Then the submerged airplane suddenly resurfaced and there was still air in it. The pilots managed to open the rear hatch, get the two gunners and the dinghy out, and I rescued my camera. A few minutes later the plane was gone, this time for good. We were soon picked up by a passing liner…”.

Three of Skorzeny’s ribs were broken and several pieces of glass had been pulled out of his shoulder. But there was no time to lie in a hospital bed. He studied photographs of the island and found military barracks on it. In the harbor, two old amphibious planes and a small rescue plane were moored to buoys. Skorzeny ordered Obersturmführer Radl to put his troops on a minesweeper, enter the harbor at night, block the soldiers’ path from the barracks to the villa, destroy the guards, and drag Mussolini out.

In the afternoon, before the night raid, Skorzeny was making a final reconnaissance. Dressed in a soldier’s uniform, he helped the laundress carry baskets of dirty laundry from the truck to the laundry room. While the laundress did the laundry, Skorzeny and his assistant Varger studied the surroundings and made final notes on the plan of attack. When they returned to the laundry room, they found a carabinieri from the villa’s security service there. He was flirting with the girl and became friendly with her helpers.

They talked, and after changing the subject to one that interested them, Varger used his trick again, claiming that Mussolini had supposedly died in a medical clinic. To which the carabinieri said he had seen the Duce a few hours earlier when he was escorted into the harbor, to a rescue plane. The small plane disappeared from the harbor, and it was a shock to Skorzeny. Everything had to start all over again.

At that time he had received a stupid order from the Führer’s headquarters to land his group on a small island near the Elbe, where the Italians were supposedly hiding Mussolini. Skorzeny realized that the order came from the strategists in the General Staff, who were preparing another “Ural surprise” for him. Skorzeny received reliable information from his informants that Mussolini was hiding this time in a high-altitude hotel in the mountains of the Abruzzi massif. It was urgent to convince Hitler of the error of his intelligence, and this could only be done in person. General Student and Skorzeny requested an audience. After receiving permission, they immediately flew to the Führer’s field quarters.

This time all the chairs around the round table were occupied: Hitler himself, Foreign Minister von Ribbentrop, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, General Jodl, and next to him the sinister Himmler, then Air Marshal Goering and Fleet Commander Karl Denitz. They were all listening to SS Hauptsturmführer Skorzeny.

“During the report, I was interrupted by Hitler,” Skorzeny recalled, “the Führer said he had canceled his order to attack the island off the Elbe and asked me to outline my plan. As he left, he shook my hand: I believe you, Skorzeny, you will do it!”.

Failure was a painful experience for Air Marshal Goering, especially now that his fleet was losing the skies over Italy. When asked how the reconnaissance planes had performed, Skorzeny assured the Marshal that his planes were so unique that they could even function as submarines. Göring laughed and they parted friends.

***

LANDING IMPOSSIBLE!

In the Abruzzi Mountains, on a plateau 2,000 meters above sea level, rises Mount Gran Sasso, which is another thousand meters high. On top of the mountain, the ski hotel “Campo Imperatore” was built shortly before the war. A funicular railway with a small carriage was built to transport guests and supplies from the valley to the top of the mountain. The funicular was the only means of transport and could only accommodate a few people. To keep the secret prisoner in that hotel, all civilians were evicted and 200 carabinieri guards, including high-ranking officers, were stationed in the facility. Another 50 soldiers guarded the cable car station down the plateau below.

Skorzeny again needed aerial photographs of the site and the surrounding area. On the 8th of September, he and several assistants flew to the site in a plane equipped with an automatic camera. The flight was kept top secret, even the pilot did not know where they were going, he received all instructions in the air. He was told they would be filming the coastline and ports. On the approach to the target, at 5,000 meters, they discovered that the control mechanism for the camera built into the belly of the plane had frozen.

They had to break out a piece of window in the lower fuselage to take pictures with the spare camera. The cockpit was cooling rapidly, so action had to be taken quickly. Skorzeny squeezed through the hole, supported by assistants holding his legs. Below them was the summit of the Gran Sasso, with the hotel visible in the distance. Skorzeny managed to take a few pictures and was dragged into the cockpit. He ordered the pilot to descend and fly north along the coast, while he warmed himself up and pretended to photograph the coastline.

Then they descended to the water and flew to their airfield. This maneuver saved their lives because that day, 8 September 1943, Prime Minister Badoglio’s government surrendered the country to the Americans and the skies of Italy were full of British and American planes bombing German bases. They landed safely at the airfield, but Skorzeny’s boys found the barracks bombed and many documents destroyed in the fire. The Americans bombed Rome day and night. All those involved in the operation realized that the situation made the mission almost impossible.

On 10 September a meeting was held at General Student. Several experienced airborne commanders were present. They discussed possible options for kidnapping Mussolini and how to approach the hotel. An element of surprise was needed, but a parachute landing was impossible – at an altitude of 3,000 meters in thin air a parachute would not open and losses would be enormous. In addition, as the sun rose, the air currents over the mountains became stronger and would carry all the parachutists to the plateau.

This left the option of landing on gliders. Studying the photos, Skorzeny spotted a small green triangle not far from the hotel. Believing it to be a grassy meadow, he considered it the only suitable place for the gliders to land. All the commanders objected, pointing out that landing gliders on the ground at such an altitude had never been done before and was therefore technically impossible.

All pointed to the expected loss of 80 percent of the paratroopers and the utter unreality of carrying out the operation with those who will remain alive. Skorzeny argued. He was convinced that if the pilots controlled the landing speed of the gliders, the chances of success would be high. General Student eventually agreed with Skorzeny’s arguments, but on the condition that the engineer would make all the necessary calculations and cancel the landing of the gliders if the situation proved dangerous.

The order was given to deliver 12 gliders from an airfield in the south of France, and day X was set for 6.00 a.m. on 12 September.

Each of the 12 gliders could carry 9 paratroopers and a pilot. All calculations were made, including the gliders’ flight and landing distances, and each glider’s landing sites were carefully calibrated. The paratroopers were armed with the latest FG42 automatic pistol, 7.92mm caliber, with a 20-round magazine. Everyone knew that casualties were inevitable and it was anyone’s guess how many of the 108 soldiers would survive against 200 heavily armed carabinieri protected by the walls of the Fortress Hotel.

Moreover, if the paratroopers were successful, Mussolini could be shot by the guards. Therefore, an Italian general was found and brought to negotiate with the guards after the landing.

But the gliders were late, delaying the operation by half a day. This delay created uncertainty at the point of attack. Enemy radio spread rumors, misleading the Italian units, that Mussolini had already been sent on a warship and handed over to the British command in North Africa. But the calculations of Skorzeny and General Student’s naval officers showed that this could not happen at such short notice, since the first Italian ship had only left Italy yesterday to surrender to the Americans.

***

“MACHEN WIR LEICHT!”.

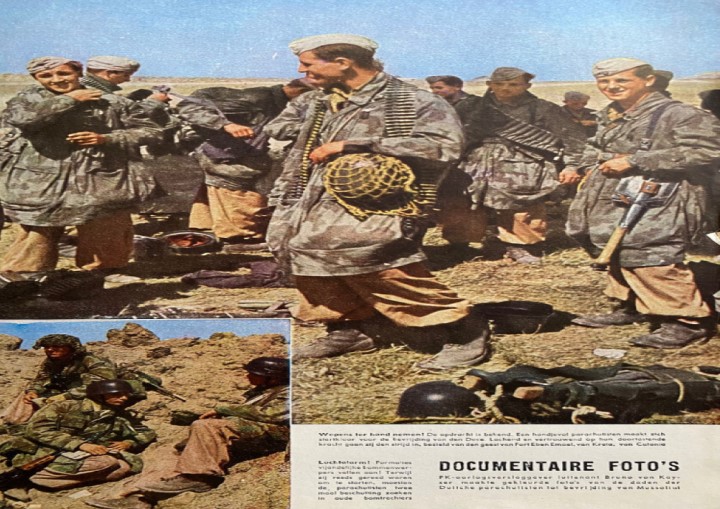

Finally, the gliders arrived, their tugs were refueled and the paratroopers were given the final instructions. General Student exhorted them with the slogan “Machen Wir Leicht!”, which later became the battle cry of Skorzeny’s paratroopers (or “Make it easy!” – in English).

The engines roared and soon the gliders were in the air. As they approached the Abruzzi mountains, they were caught in a cloud cover that helped their camouflage. When they reached their destination, the tow ropes were released and the gliders lined up for landing.

And then it turned out that the first two gliders, whose paratroopers were supposed to cover the others immediately after landing, had disappeared!

The gliders had probably crashed into the rocks. Not wanting to repeat their sad fate, the paratroopers cut the canvas sides of their gliders to improve visibility. They emerged from the clouds at their destination, the sun illuminating a scene that made Skorzeny uneasy. The green patch was not a meadow or a grassy slope. They were pine-covered rocks, good for slalom skiers. Skorzeny remembered the General’s order not to make an emergency landing in an unforeseen situation and to abort the operation. But it was too late. He called over the radio for all the pilots to follow him and land as close as possible to the hotel!

His glider did not land but fell 15 meters from the hotel. The others, like dragonflies, fell from the sky one by one, paratroopers jumping out of them and shouting “Hende hoh!” to the dazed carabinieri. The guards were in total shock, no one tried to resist. Skorzeny and the first group burst into the hotel and the first person he saw was the radio operator, frantically banging on his key. Skorzeny smashed the radio and the group of carabinieri his paratroopers encountered were pushed into the room and locked in. The head of security was ordered to lay down his weapons.

The officer asked for time and Skorzeny gave him one minute, adding that after that the course of events could become unpredictable. The Italian general added credibility, and a telephone from the lower station of the suspension railway reported that it had already been taken by the paratroopers.

The head of the guard left and returned a minute later with a bottle of wine to present to Skorzeny as the victor. The guards were allowed to keep their personal weapons; their rifles and carabines were locked in the room.

The stunned Duce was taken by cable car to the lower station, from where Skorzeny took him in a small plane to Rome, on to Munich, and on to the final destination – Hitler’s headquarters.

After the operation, Skorzeny was promoted to SS Sturmbannführer and awarded the Knight’s Cross. Goebbels’ propaganda dubbed him “The Diversion Number One” and Winston Churchill called the operation “extremely daring”.

Indeed it was. Skorzeny gained absolute authority in Hitler’s eyes and was involved in all sorts of special adventures until the end of the war.

***

His last military operation took place in the Ardennes at the end of 1944, after the Anglo-American troops had landed in Normandy. His three thousand saboteurs, dressed in American uniforms and driving trophy tanks and lorries, broke into the enemy rear. The panic and chaos they caused completely ruined the Christmas celebrations of the Anglo-American commander of the combined forces, General Eisenhower.

In the last month of the war, Skorzeny was in southern Germany. His mission was to mislead the enemy military command about the alleged transfer of the Führer’s headquarters to the Alps. After Germany surrendered in May 1945, Skorzeny surrendered to the Americans.

After two years in the Dachau prison camp, he was brought to trial:

“…Accused, the Supreme Court has information that you were preparing to kidnap General Eisenhower, commander of the Allied forces, to kill him!”

“…Gentlemen of the Court,” he stretched out his six-foot frame above the bench, “may I ask what is the basis of your accusation? Do you have any evidence? You can’t have any because there was no such plan. Many people, including yourself, know that the Reich High Command sought an alliance with you against Stalin’s Bolsheviks, and in that alliance, your General Eisenhower was our potential ally, not our enemy. So why would I have killed him…”

“…We also have information,” the judge raised his hand warningly, “that at the Battle of the Bulge, soldiers of your unit used American military uniforms to mislead the enemy. Such a violation of the Geneva Convention on the Conduct of War is punishable…”

“…Your Honour, there is some truth in this,” replied the defendant, “it was winter, my soldiers were completely frozen in the mountains and we used the enemy’s clothes in the campaign. But before the attack, the soldiers were ordered to take off these foreign clothes. We did not violate the terms of the convention…!”

Here he was “inadvertently” helped by an English officer who confirmed the fact of the use of enemy uniforms and by the English soldiers.

The case was dropped, and Skorzeny’s actions were classified as those of a soldier following orders. He left the courtroom. In his cell, he put his personal belongings in a satchel and walked out the gate. No one stopped him.

AFTERWORDS.

Hitler’s commando, the executor of secret operations in many parts of the world, Otto Skorzeny was a legend of the Third Reich. He committed no war crimes and was acquitted by a military tribunal. He lived a long life and had many adventures. Several of his memoirs have been published. After Skorzeny’s death, his daughter inherited, as she put it, “…a whole cubic meter of my father’s documents and personal papers…”. Hopefully, we’ll learn more about them in the new books. The adventures of “Long Otto” continue…

© Copyright: Walter Maria, 2017 Certificate of publication #217080700124

Be First to Comment