From the author.

It’s hard to express feelings without expressing emotions. But I’ll try. This is the story of a sailor’s fate. The truth burns like pure alcohol, which not everyone can drink. So it’s watered down with fiction and sweetened with lies. But I’m old-fashioned, I was never taught to lie. So I will pour you the truth as it is, undiluted.

In all civilized countries, seafaring has long been considered a high-risk profession. Seafarers are protected by an international trade union, guaranteed high wages and various benefits. The International Trade Union did not protect Soviet sailors and fishermen. With all the resulting, as they say, disenfranchisement. Because the Soviet political system is feudalism and they are far from civilized countries.

They say that a fisherman is twice a sailor. Soviet fishing trawlers used to go to sea for fishing, the voyage lasted for half a year. The main food of fishermen was frozen meat, tinned food, and cereals. The meat was from the army fridges, where it had survived all the expiry dates. Fresh fruits and vegetables were not part of their diet, as Soviet fishing companies did not spend money on replenishing stocks in foreign ports. In addition, their diet included freshly caught fish which helped. Only in six months, after the end of the fishing season, the trawler was allowed to enter a foreign port for a day or two, where the fishermen were given some money in local currency. The crew was taken into town in small groups for a few hours under the supervision of informers. There they had to proudly present the image of the country of victorious socialism and, of course, avoid drinking places, taverns, and bars.

When they returned to the ship, the crew and the goods they had bought were inspected. In their home port, the ship and the fishermen were searched again by customs officers and border guards with dogs. There was a Soviet song ‘Where the Motherland Begins’. For the sailors, it began with a search for contraband. The fishermen were not supposed to arouse the envy of their fellow citizens with jeans bought from the damned bourgeoisie. They had to heroically overcome the difficulties of their profession and receive the modest wages of a Soviet worker. There was no compensation for risks or injuries. The fishermen’s adherence to the moral image of a builder of communism was closely monitored by the ever-present and omnipresent KGB, which had its eyes and ears on every ship that sailed the distant seas.

===== =====

PART 1. WHY A SEAGULL WALKS ON THE SAND…

Leha’s childhood smelled of the sea and campfire smoke. There was also the music of Giuseppe Verdi. Leha’s mum loved classical music, especially opera, and all boys love what their mothers love. Historians claim that the great Italian began studying music and playing the organ in the local church at the age of five. Coincidence or not, when Leha was five, a family friend, the conductor of the local symphony orchestra, began teaching him to play the violin.

Leha grew up an inquisitive boy, learning to read at the age of four, and with a good ear for music he found it easy to learn it. When he was not accepted into primary school at the age of six, he cried bitterly, he wanted to learn. But he had to wait another year. He studied at home. The following year he was admitted to school, and in his first lesson, Leha surprised the teacher by beginning to read the textbook fluently. Two weeks later he was promoted to the second grade. This allowed Leha to catch up with his friends who had started school a year earlier. But even in the second grade, he was bored. And in the third too. Leha finished four years of school with honors. With his mum he spent that summer in the Caucasus, at his grandfather’s home. For curiosity and success in his studies, grandfather honored him with a gold family watch. It had Roman numerals on the dial, an antique watch that his grandfather had inherited from his father.

His beloved mother died tragically in September. Leha had already lost his father. The authorities put him in an orphanage and his childhood was over. All the children in the orphanage are like mad dogs. Leha got into trouble and realized that in his new life, strong fists would be more reliable than a violin. He began to learn boxing, running five kilometers to training school in the city and soon had a good punch in both hands. Leha became a biting dog, learning the lessons of survival. He beat his tormentors painfully, and soon even the older pupils began to fear him. After the 8th grade, Leha was expelled from the orphanage. The headmaster was a kindly uncle, a front-line soldier. He taught chemistry and the orphans nicknamed him Plumbum:

“You ruin discipline and set a bad example for the other pupils,” Plumbum looked at Leha sternly, “that’s why you’re expelled. If I give you an F for behavior, I’ll have to send you to a work colony. You’ll be lost there. You have studied well, and you have even been an excellent student. So I’ll give you a C-minus and you can decide how you want to live from now on…”. Plumbum handed Leha the certificate and closed the door behind him.

***

Leha was fifteen years old. To earn a living and help his old grandmother, he got a job as an electrician’s apprentice in the factory and continued his studies at night school. He had to give up boxing, he got too busy with life things. Leha punched with both hands and his trainer persuaded him to stay, promising him a sporting career. But Leha had other plans. He dreamed of the sea, and the next year he enrolled in a nautical school and passed all the entrance exams. The nautical school prepared specialists to work on the merchant ships of the Black Sea Shipping Company. Leha began a new life, the happy days of a cadet. The cadets sailed from Odessa to Ochakov, to the island of Berezan, and back on paddle yachts. They competed to be the first to cross the finish line, and victory was accompanied by a sweet ache in the strained muscles.

Every six months the cadets were sent to sea for training. They did this on trophy passenger ships sailing from Odessa to Batumi and back. The route was called the Crimean-Caucasian route, but the cadets nicknamed it the Crimean-Kolyma route. For them, the day began with scrubbing the decks, which had to be sanded from rusty sweat to amber glow. Storm waves flooded the ship, which had served all its days, rust flowed on the decks, and every morning for the cadets began the same way. This was their Kolyma (in the USSR place where long term prisoners were sent). The practical training was a test of fitness for the job, and not everyone passed. The sea loves the strong in body and mind, weaklings have nothing to do there. After returning to Odessa, some of the cadets disappeared running away to their home village. There it is not stormy and the cow’s tits are always full of milk.

Vasily Ivanovich Volobuev, a long-distance captain and a romantic in love with the sea, taught them the basics of navigation. He taught the boys to navigate by compass, read watch logs, understand the nature of currents and tides, and feel the wind. The captain taught them the signs of the sea: “If the sun is red in the morning, it means a change of weather is coming.” If the sun is red in the evening, the sailor has nothing to fear.” “If the sun hid in a cloud, a sailor should expect a storm at sea.” “If a seagull sits in the water, expect good weather.” And “If a seagull walks on the sand, a sailor is troubled at heart.”

The last omen especially intrigued Leha. So he asked the captain what the seagull was pining for. The old sailor smiled: “You see, Alexei, according to the legends of the Vikings, the first brave seafarers, the souls of dead sailors move into these seagulls. Seagulls are always at sea, and when they fly over the masts, it means that your ship is on a safe course. I wish you never to see a seagull on the sand…”.

Leha learned to read the sea and the stars and to smell the wind. Later, in his adventures at sea, he will pass through heavy storms and hurricanes, and survive in Antarctica and the treacherous waters of the North Atlantic, where rocks and reefs lurk in the thick fog off the coast of Ireland. He will remember the the compass cartouche taught to him by his couch, he will learn to navigate sea ships and one day become a captain himself. But that will come later.

***

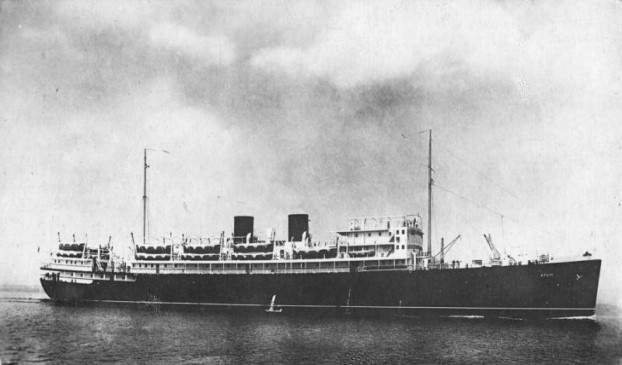

His first maritime experience was on the passenger liner ‘Admiral Nakhimov’. It was an exceptionally beautiful trophy liner ‘Deutschland’ that the USSR had received after the war and re-named. The shipping company had no legal documents for the liner, so it was not allowed to go further than the Bosporus. The liner carried Soviet tourists around the Black Sea.

The god of the deck crew was the bosun Stepanych, who looked like a real pirate from Stevenson’s stories: hands like hooks, an animal grin on his face. But Stepanych had a golden soul. He loved his boys and taught them the sea profession, taught them hard. And there was no other way to teach them.

Early in the morning, they approached the Georgian port of Poti. The bay there is shallow, so the berth for ships with a decent draft stretches out to sea. It was stormy, and Stepanych ordered all the cadets to go down to the forepeak to knit mops. The amplitude of the rocking is the greatest in the forward part of the ship, and it is in the forepeak it is felt in full measure. “You have to beat out the wedge with a wedge,” laughed Stepanych. This was his way of accustoming cadets to the sea rocking.

The wave in the Black Sea is high and steep, there is not much room for acceleration, not like in the ocean. And then it happened. The wave rocked the liner and at the entrance to the bay it hit the keel against the ground. Good thing that the bottom of the bay was muddy, the hull withstood. The cadets flew out of the forepeak onto the deck. Bosun Stepanych looked at his bewildered charges and laughed. The alarm was sounded and they prepared to start patching the leak. But there was no leak. The Germans built ships of high quality, like everything else they made.

It was December, the season for persimmons and tangerines. All these fruits were cheap at the local market and the cadets ate them. Leha was one of the three helmsmen, the “white bones”, as they called those who kept watch in the wheelhouse and on the upper bridge. He knocked on the bosun’s cabin on an official matter. Stepanych opened the door and Leha’s nose was assaulted by aromas. The whole deck of the cabin was littered with boxes and crates of persimmons and tangerines. The cabin smelled like the Garden of Eden. Seeing his consternation, the bosun laughed:

“…Leha, my wife likes to make persimmon jam, so I’m bringing home Christmas presents. Why don’t you make some for your family?

“No family, Stepanych. I hadn’t thought about that,” Leha hesitated.

“Listen to the old fool, boy,” the bosun hugged him. Buy this citrus with all the money you have, it’s worth a penny here! You’ll sell it for five times as much in Odessa because we’re coming home on New Year’s Eve. And you’ll have some funny rubles for the holiday, for wine!

“Stepanych is right, and why not,” Leha thought. He bought persimmons and tangerines with all his cadet money. In Odessa, in the first restaurant, they bought everything from him and asked for more. The roubles crunched in his pockets and Leha wanted to go back to Poti to repeat the purchase. It was his first business. “The money is a virus!” smiled Leha.

He was on night watch, on the gangway. Tomorrow the ‘Admiral Nakhimov’ would leave for Varna. But Leha had no visa. They say, “A chicken is not a bird, and Bulgaria is not a foreign port!” But KGB wouldn’t let Leha go there either. “Assholes!” he lighted a cigarette and blew out the smoke.

It was drizzling, and the snow that had fallen during the day turned to mush underfoot. This is winter in Odessa. At the neighboring quay, a dry-cargo ship from Beirut was unloading its cargo of oranges, bound for Moscow, onto a freight train. The smell of citrus fruit hung over the quay. Leha could see from above how a loader was dragging a crate, obviously stolen. Then a police whistle blew. The loader dumped the crate and ran up the gangway, straight for Leha:

“Hey, kid, where to run, help me!” The burly man was breathing heavily, and behind him, a policeman was clumsily climbing up the gangway. Leha didn’t like policemen.

“…Run over the superstructure and jump into the water there…” he whispered to the loader, showing him the way.

In a few minutes, it was a body splash and a gunshot. A scowling policeman came down the gangway. The fugitive was gone, it was a dark night.

The next day, Leha was drinking wine with his mates in the local bodega. A tall man in a raincoat smiled at him from a table in the corner. He looked very much like that night loader.

As the evening wore on, Leha remembered the story and decided it was better to trade than to steal. However in the USSR, entrepreneurship was a crime, and all street traders were considered speculators and criminals. They were in the same bunk as thieves. The population was ordered to work in factories and plants. Except, of course, the wives and children of the party bosses. These were privileged not to work, for them, communism had already come. By looking at these idlers, the whole population was lazy to work. People used to say: “…they pretend to pay us and we pretend to work…”. There wasn’t enough money from one payment to the next, so they borrowed from their neighbors. That’s how all Soviets lived.

His next maritime practice was on the steamer ‘Crimea’. At the beginning of its life, the ship ran on coal, then its furnaces were converted to diesel fuel. The old ship smoked badly. During the Civil War, she probably carried a White Army soldier to Turkey. Now it was a voyage on the Crimean-Caucasian route, from Odessa to Batumi and back. The Yalta film studio chartered the steamer. The ship was repainted in black and white and the name “Tsesarevich” was written on it. Famous actors Nikolai Kryuchkov and Svetlana Svetlichnaya took part in the filming.

At sea, the ship groaned under the waves, all its rivets and bulkheads creaked, and only the god of the sea, Neptune, knows why it did not sink. This was the veteran’s last voyage, and on his return to Odessa, she was sent to be dismantled. Madame Svetlichnaya Leha was seen only once, probably she was too shy to appear on deck. Or perhaps she was seasick. And the cadets didn’t see the cameramen either. But Nikolai Kryuchkov was always in sight. Happy and gregarious, he loved the sea, and the sea and the sailors loved him. He was a man of great kindness. Cadets called him “Uncle Kolya”.

In Yalta, the city of aromatic Crimean wine, Uncle Kolya had drunk a little too much of it, and the hot sun overheated his head. The cadets carefully hold him under his arms and helped him up the gangway to the ship. And Uncle Kolya was hugging them and saying: “…you are my boys, my good ones…”. He was a good man. And a good actor! And a real sailor, he never got seasick!

In Batumi, the cadets were sent to the funeral procession. They were burying Nadya Kurchenko, a local airline stewardess who died at the hands of Lithuanians who hijacked a plane bound for Turkey. After his mother’s death, Leha could not hear the wailing of the funeral orchestra, it was beyond him. He escaped to the embankment. There, palm trees hung their huge leaves, birds fluttered and whistled in them, the smell of the sea mixed with the smoke from the kebab shops. Leha sat down in the shade and smoked. His thoughts were of the killed stewardess:

“Why did you resist, you fool? You could have lay down quietly on the floor like all the other passengers, and today you would have raised your children and smiled at the sun. But now, instead of sunshine, there will be darkness and cold, where your flesh will be eaten by worms, and no one will remember you..”

She must have been a pioneer and a Komsomol member. All fanatics have the same end…

“Hey, sailor, gild my hand, I’ll tell you the whole truth,” the gypsy interrupted his thoughts. Leha rummaged in his pockets and handed the fortune-teller three roubles, a cadet’s monthly stipend. It was money, after all: a packet of cigarettes cost 20 kopecks, a bottle of wine one ruble. The gypsy woman drew her finger across his palm, then looked strangely into his eyes:

“… Go with God, handsome, God bless your destiny,” without taking his money, she disappeared as suddenly as she had appeared. Many years later, being in trouble, Leha often remembered that gypsy woman. But at that time he paid no attention to her words. His adventures continued, and he dreamed of the Bosphorus.

***

Four excellent students stood in front of a row of six hundred graduates of the naval school. The rumble of the drums and the wailing of the orchestra frightened the sparrows away and they hid in the leaves of the flowering acacia trees. Excellent students received diplomas and commissions on the best ships of the Black Sea Shipping Company’s merchant fleet. Two of them were particularly lucky: they were sent to be part of the acceptance teams for newly built ships. Being part of a ship acceptance team was like hitting the jackpot at the casino in Monaco. The two-month trip to a shipyard in Germany meant money that could be used to buy a council flat in a good area or the most prestigious Soviet car, the ‘Volga’. The amount of money the sailor received on such a business trip was beyond the reach of nine hundred and ninety-nine out of a thousand of his compatriots. The lucky ones were applauded with envy. But not all four were rewarded. The awarding officer averted his eyes and sent Leha to the personnel office.

There Leha was given an envelope with an unknown office called “CherAZMorPut” on it. The office was not far away, around the corner, in a shabby one-story building. An elderly woman took an excellent diploma from the envelope and stared at Leha:

“…Boy, there’s an obvious mistake here, go back to your personnel department. We’ve got drunks, smugglers, … the bottom of the fleet!”

Leha smiled crookedly: “…the papers are in order, please, hire me.”

Having received his ticket to life at sea, Leha set off on ‘Primorsky Boulevard’. The bronze founder of Odessa invited him to the blue sea with a friendly gesture; pigeons made love on the bronze duke’s head in broad daylight, in full view of pedestrians. His best friend in Odessa was Zhorik. They lived not far from each other and studied at the same college but in different departments. They both loved rock music, these were the years of the famous Liverpool Four. They formed their band at the college, Leha was the drummer, and Zhorik loved the guitar, and it sang in his hands.

The system didn’t give Leha a visa because he was an orphan. The system didn’t give a shit about his honors degree. Leha had no hostages on whom the system was to take revenge when a sailor who was out of the country decided not to return. His friend Zhorik was denied a visa by the system because his father was Jewish. His mother was Ukrainian. Such people are not considered full-blooded Jews in Israel. That’s the reality of Marxism-Nazism. People don’t understand it today.

Leha opened a bottle of beer and smiled at the bronze duke. In two days he would fly to Kerch, wherein the cargo port, his small ship was rubbing its rusty side against the quay. Looking at the statue from the side of the Pushkin monument, the scroll in the duke’s hand resembles a protruding masculine “dignity”. An observer of socialism from the first days he pointed to the sea with one hand and held his “dignity” with the other, consciously alluding to it:

The sea is sparkling,

But the fog is thick

Dreaming of a visa?

Suck my dick!

The next morning, after the graduation show, Leha went to Zhorka’s place. Together with their friends, they went to their favorite wild beach. There, in the coastal rocks, they had a stash – a couple of bottles of dry wine and a piece of tin on which they roasted their catch of mussels and crabs. The crab is a silly creature. If you tease it with your right hand, it will try to grab your finger. And then with your left hand, you have to press the crab from behind into the sand. Got you, you fool!

Zhorka rubs his eyes…. is he crying?

“It’s nothing, the salt stings,” he laughs.

Leha knows that Zhorka is in as much pain as he is. They dive into the salty sea. To hell with the KGB, life goes on!

KERCH.

The dredgers are cleaning and deepening the channels, and the shuttles are taking the mud out to sea and drowning it in the designated areas. The shuttle captain took Leha’s papers and sent him to the bosun. He showed him a bunk in a four-berth cabin and said he should be ready to go to the dredging site tomorrow.

That evening, Leha was at dinner with his new friends. According to tradition, he put two bottles of vodka on the table. Three of the boys were his age, obviously not trained to drink, and they got drunk quickly. Leha suggested they take a walk along the seafront to get some fresh air.

“Boys, Kerch is a bandit town. There are no serious bandits here, just scum, but it’s better not to go out in the dark…” the bosun warned.

On the table was a galley knife for cutting meat, a weapon of terrible beauty. After the bosun’s warning, Leha couldn’t resist and slipped the knife into his sleeve, just in case.

His new friends noticed and scattered the table knives in their pockets.

“Guys, don’t do that,” Leha laughed, “it could ruin your life. I know, I’ve been in street fights, I’ve smelled bloody shit you haven’t smelt…”.

But the sea is knee-deep for drunks.

The two pussies walked in front of them, enticing them with their asses. They followed them, and soon the girls led them to a dead end. Several people were waiting for them there:

“Ahhhh, so you want to hurt our girls?” said the tallest of them, “It will cost you all your money, assholes…!”. He defiantly tried to attack Leha.

But he didn’t know who he was attacking.

“…You filthy bitch, you’re attacking Odessians…?” Leha pulled a knife out of his sleeve, and the attacker’s eyes began to glaze over at the sight of the knife.

The knife was scary, and even scarier was Leha himself. He swung the knife in his right hand and hit the scumbag in the head with a left hook. The scumbag collapsed on the asphalt. One of Leha’s drunken buddies jumped up and added a boot to his head. That’s not necessary. Leha orders them to hail a cab.

The scum lays unmoving, his partners in shock, probably thinking Leha had killed him.

“If anyone moves, you’re dead!” – Leha shouts to them, and they press themselves against the wall.

The girls on the bench are silent. When Leha passes by, he grabs them by the hair and pushes their heads together. They howl in pain. No, he probably didn’t hit them as hard as he wanted to. Otherwise, their brains would have fallen out.

***

PRIVATE CHUGUEV.

In the autumn, Leha received a summons from the military commission in Odessa. He was to be drafted into the army. The army did not require a visa. He went to his hometown of Odessa. In the office, the military officer pounded his fists on the table:

Chuguev, you must do your duty to the Fatherland and the Party. You have the honor of serving in the submarine fleet, in Sevastopol. Since you are a trained sailor…!” he finished.

Leha left the office and lit a cigarette. He agreed with the duty to the motherland. And he owed nothing to the Party. He wore a pioneer’s tie, but he was not a member of the Komsomol. And now he didn’t want to give years of his life, maybe even his life, to this party. Besides, he liked surface ships and the blue of the horizon. And you can’t jump out of a submarine or a plane in an emergency. So he was late for the draft, a day late. The officer was furious. He promised to send Leha to a place “where Makar would not graze his calves”.

He didn’t lie.

The train rattled its wheels across the deserted snow-covered plain, over which forests were blackened and crows circled. The well-tended Ukrainian gardens and groves were far behind. It was November, and it was already winter in Russia. Outside the windows, Leha glimpsed dilapidated huts propped up with sticks and covered with blackened straw. Leha thought that the soldiers of Napoleon’s army were still inside these barns, trying to escape the cold. Makar did not graze calves here; the officer was right. Leha found himself in the eighteenth century.

They were unloaded onto a platform in the middle of nowhere. Women walked in dirty cotton coats, men kneaded mud with boots, blew their noses, and wiped their fingers on their trousers. Everyone was drunk. Leha remembered the cadets of his marine school who had come from Russia. They would wipe their arsis with their fingers and then wipe their finger on the wall in the crew toilet. They were caught and forced to lick their artwork off the walls.

In this remote area, there was a military unit where Leha was to fulfill his duty to the Motherland and the Communist Party. The battalion of three companies was commanded by a major, and his deputy was a lieutenant colonel, an elderly man. He called himself a front-line soldier, but he had only jubilee honors and had spent the whole war on the home front. Since he was higher in rank than the unit commander, he resented being subordinated to a major. The old fart’s views were narrow and primitive, and to the young soldiers, he was full of arrogance and ambition. Having been an educated sailor and now a reluctant recruit, Leha teased him with provocative questions in political classes. He often stunned the lieutenant colonel, the old fart’s face poured blood, and he sent Leha to the brig.

In the soldier’s trade, Leha quickly learned the automatic rifle and performed day and night shooting with excellence. He regularly ran a dozen kilometers on skis with guys from the sports company, took part in army sports competitions, and twice went to military district exercises. But he was not given an excellent service badge. The badge was intended for excellent combat and political trainees, who were considered zombied by propaganda and were ready to give their lives at the first order of the commander. Leha was excellent in combat training but bickered with the deputy politician in matters of politics. And did not want to be zombified. For this, the political officer had often sent him up in the brig.

At the end of the summer, a company of sturdy soldiers was sent to a logging camp in the Kalinin region. They lived in tents in the forest. It was August, the water in the buckets froze overnight, and to wash you had to hold the bucket over the fire for half an hour. Food supplies were irregular, and the thermos flasks contained a mixture of rotten vegetables and scraps of meat. For two months Leha wielded an axe on the logging site, experiencing first-hand the so-called ‘heroism’ of the Komsomol construction sites that journalists talked about on the front pages of the Kremlin newspapers. The work for the Komsomol on these sites was done by convicts. They did not sing Komsomol songs, but prison songs, and their whole life was reduced to survival in dog-like conditions.

Leha played guitar and drums in a soldier’s rock band. He knew how to work with poster markers and cardboard, and decorated classrooms. In general, he was clever. At the very beginning of his service, Leha was sent to sergeant courses. But the same lieutenant colonel canceled his studies and the badge of excellence in combat and political training. For him, Leha was an anarchist and anti-Soviet. By the end of his service, Leha had accumulated fifty days in the brig, all for quarreling with the lieutenant colonel. The lieutenant colonel wanted to destroy the rebellious soldier by sending him to a disciplinary battalion. And then an officer from the special department (military KGB) decided to recruit the rebellious soldier as an informer by blackmailing him.

One evening Leha was called to the headquarters. An unfamiliar officer was waiting for him in the unit commander’s office. It turned out to be the same officer from Special Branch.

“You’re not a bad soldier, Private Chuguev,” the officer began from a distance. Noting Leha’s efforts and successes in military disciplines, he moved on to blackmail:

“But the deputy commander considers you a persistent violator of regulations and an anti-Soviet. You have 50 days in the brig, all because you are a troublemaker. Are you anti-Soviet? We can easily send you to a disciplinary battalion. There you will learn to love your country!”

Here Leha remembered Plumbum’s warnings from the orphanage.

Having stunned Leha with threats, the officer moved on to recruitment. He offered to inform on fellow soldiers and officers. Leha was shocked by such blatant insolence to turn him into an informer.

Lying in bed after lights out, Leha did not sleep a wink. He knew there had been embezzlement and shortages in the unit. The thieves were petty officers, freelancers, and local alcoholics. But Leha didn’t care about them.

This was the army, and to him it stank of a disciplinary battalion, a prison. He’d beaten up snitches in the orphanage. So the only thing left to do was to play the fool. The next time the KGB officer came to the unit and asked his questions, Leha answered like those three monkeys “I didn’t see, I didn’t hear, I don’t know”. And the officer finally let him go. And then came the end of his service term.

One evening Leha was called back to headquarters. This time it was the commander of the unit who addressed him:

“Private Chuguev, I’ll be frank. If I send you to the disciplinary battalion, as the lieutenant colonel insists, I will not get the next rank, a star on my epaulets. And there’s no telling how long the delay will be. So thank fate that your service has come to an end. The order to demobilize you has been received. It would be better for you if you disappeared immediately”.

The major handed Leha a package: “Here is your military card and a prescription for the military draft office in the place where you were drafted. Your service is over. I’ll give you twenty minutes to pack and leave!”

“Dear Commander! Ten minutes would be enough for me!” Leha saluted with one hand, grabbed the package with the other, turned on his heels, and flew out of the office.

***

At the military registration office in Odessa, Leha got a mark on his military card and was enrolled in the reserve. He went to the Primorsky Boulevard. The sea was bright blue. And the sky was the color of the sea. Leha smiled at the Bronze Duke, who seemed to be winking at him. And it was so good for the soul! He was home, after all, and the sea was so close!

He visited his marine school and found the group commander:

“Valentin Stepanych, you were my teacher and I still asking you for help. What to do? I’m a sailor, and I want to go to sea!”. They stepped outside for a smoke.

“Alex, you’re already twenty. You’ve been to an orphanage, marine school, and the army. With all that, you should know the world you live in better than any of your contemporaries. But I see that you are still a naïve boy, you still are”, the commander took a puff on his cigarette.

“You should understand one thing, Leha,” he went on, “you have no relatives, so the system doesn’t believe you. You’re like a free wind, and once you’ve seen a normal life beyond the seas, you’ll run away one day, nothing will hold you here. In short, if you want to see the Bosporus, you have to get married and make a child as a hostage for the system!” he slapped Leha’s knee with the palm of his hand and ended the conversation by adding, “Forget about that rotten ‘Black Sea Shipping Company’, there are only hoarders and snitches there. Go to the Fishing & Whaling Company! They always need real seamen. You’ll find your way there!”

Leha grinned: “I remember your admonition, you wrote it on the back of my graduation photo: ‘You did your first step right. Let the second be the same!”

“So take that step, Alex!” the commander smiled at him.

***

Life showed that the commander had given him the right advice. A month later he got married, and when his son was born he applied for a visa to the whaling company. He soon received a note from the personnel department that he also needed the recommendation of the military unit in which he had served. Leha remembered the lieutenant colonel, fifty days in the brig, and it scratched his soul. But there was no choice, so he bought a ticket on the train.

Nothing had changed around the military unit – the same boots, the same mud, the same drunken faces of men and women. At headquarters, he knocked on the door of the commander’s office. A young captain sat behind the desk, and there were changes all around.

“Chuguev Lekha? I remember you and your guitar,” the captain smiled at him. He used to be the commander of the second company. They chatted about this and that while the lieutenant girl typed up a recommendation for Leha.

“Yes, as you can see, we’ve changed here!” The captain looked out of the window, “You were here, so I can tell you about the changes. The lieutenant colonel who harassed you turned out to be a nuisance, writing denunciations about our officers to the political department of the district. The commission came. The whiner was retired. Our commander was promoted to lieutenant colonel and transferred elsewhere. So life goes on, Leha. Your recommendation is ready, but you’ll have to get it endorsed by the district political department. Good luck, man!” he shook Leha’s hand.

A few months later, Leha received a call for an interview. The Antarctic Whaling and Fishing Fleet Department was located in the very center of Odessa. In the office, he was stared at by a muzzled KGB: “The Party places its trust in you, sailor. We authorize you and hope that you won’t let us down”.

Leha had waited a long time for his sea. Now they were lending it to him. In exchange for a hostage son. Sons of bitches!

ATLANTICA.

Leha joined the crew of a fishing trawler. The voyage was to the Atlantic Ocean, south of Africa. Early in the morning, Leha stood watch with the XO, the course was the Bosporus. Leha’s heart was pounding, he saw another world in the strait – minarets, St Sophia’s Cathedral, snow-white villas. Boats and small ferries crossed from one shore to another, oblivious to his trawler. Music was everywhere. On the Asian shore, work was beginning on a bridge that would soon link Asia with Europe. After changing his watch, Leha drank his tea in a hurry and went up to the upper bridge. The Bosphorus never let go, Leha was turning his head, he was in another world. Next came the Sea of Marmara, then the Straits of Dardanelles. The water was turquoise and the islands smelled of flowers and pine needles. There were no such scents in the Black Sea. At night Leha fell asleep at once and slept peacefully. His dream had come true.

Beyond the Bosporus

In the Sea of Marmara

Once, was sinking the moon

In the haze of Bosporus

In the Sea of Marmara

Islands smell chamomiles

Beyond the Bosporus

In the sea of those flavors

The seafarer’s soul lives

She was a sea witch and diva

Her lips smelled of those daisies

She drugged my head with her kisses

And I drowned in that moonlit Bosporus…

Fishermen have long voyages at sea, half a year without land. Leha stocked up on books in the company library. He took with him the works of the classics, poets, and philosophers. The librarian soon recognized him, noticed his neatness, and offered him rare books. Leha was much calmer at sea than in a human anthill on land. His favorite works and books were at sea. But the system was watching, breathing down his neck. Every ship had a first mate, also known as a KGB informer or ‘Pompa’. Just as in the Red Army in the early years of the Soviet regime, there were Cheka commissars under regimental commanders. On the trawler, the pompa was an exact copy of the army lieutenant colonel. His job was to keep an eye on the entire crew. When a trawler returned from a voyage, the pompa would submit a detailed written report to the KGB’s Special Department. Because Leha would not play domino in the company, preferring it to books, the ‘pompa’ wrote in his characterization that he was ‘unsociable’. In other words, Leha was not like other Soviet sailors and was therefore a suspect.

The first mate of the captain, or political assistant, or ‘pompa’ in sailors’ jargon, was a Jew. The head of the food service was also a Jew. Lekha remembered his Jewish friend Zhorik, who had been refused a visa because of his nationality. Zhorka’s mum had died, she was a wonderful woman. His father took him to Israel so that he wouldn’t get drunk. Although Zhorik’s mother was Ukrainian, even in Israel he was probably not accepted as a natural Jew. Eventually, Leha lost touch with his friend.

These scoundrels ‘pompa’ and the head of the food department were given not only visas but also financial positions. They did not graduate from maritime colleges. They used the back door for their careers. Cunning and guile do not require intelligence. Under Soviet socialism, the cunning ones were always and everywhere first. Zhorik used the front door, that’s why he failed.

When the trawler was being prepared for a long voyage, the chief of food received supplies from the bases. Provisions for a six-month voyage for a crew of 80 included tons of frozen meat, and an assortment of tinned food. The food chief could sell some of the food illegally, and some took advantage of this. That is, stealing from the crew. A swindler’s eyes always give him away. This one had his eyes running. Leha thought that such people should be hanged without trial.

The captain’s first mate in the Soviet merchant fleet was not a sailor. He was a dog of the regime. He gave compulsory propaganda lectures to the crew, monitored every sailor, recruited informers, spied in foreign ports, and photographed warships and installations. After a voyage, he handed in his detailed denunciation to his boss in the special KGB department of the directorate. He was paid a captain’s salary, which he earned from the fishermen he had monitored and betrayed.

Leha knew one of them personally. They were neighbours, and they lived in the same district. With access to official information, that first mate robbed the houses of sailors who were at sea. His wife was his partner, standing on alert guard while her husband stuffed suitcases with stolen goods. It was their family business. During the journey, this thief would lecture the crew about the morality of a Soviet man, about having a clear conscience, and other such nonsense.

When he was caught stealing, he was quietly removed. He was transferred elsewhere without trial or publicity. The system doesn’t give up its dogs.

After 6 months of fishing, the trawlers would go to Las Palmas in the Canaries for a few days and anchor in the outer roadstead. The crew would be given some currency to buy some junk in local markets. The sailors were divided into groups, and when half the crew went into town by boat, the other half were kept busy doing cosmetic work on the trawler, painting the rusty sides. In each group were snitches, members of the Communist Party. In town, the group went from shop to shop. A step aside could be seen as an attempt to escape, the snitches reported everything to the first mate, who wrote a denunciation to the KGB special department. When the shopping was done and the bags filled, the groups were returning to the harbour, and the locals laughed at the savages from the communist paradise. On board, the sailors were inspected by a special group, led by a first mate. They unpack the bags and rummage through the rags they had bought. It was the same system routine all over the Soviet fleet.

***

While waiting for the next trawl to be hoisted, the sailors sat in the hold, smoking and chatting about various things.

‘ We’re waiting here and the first mate catches his fish,’ spat one, ‘he searches our things, looking for contraband. I caught him doing it once, in my cabin,’ he stubbed out his cigarette angrily.

‘ Well, what’s the use of gossiping, let’s go to the captain!‘ – Leha stood up.

There were five or six brave men. But in the captain’s cabin, Leha alone made a general complaint, while the others sat with their eyes downcast. They had betrayed him with their silence. The captain listened to the complaint, summoned the first officer and the XO and suggested that the complaint be repeated in their presence. Then he let the entire delegation go. But Leha was asked to stay.

Leha was a senior helmsman and always took the helm in difficult conditions. Cap respected him as an experienced sailor. But Leha didn’t know that the captain was having an affair with the barmaid. The first mate knew about that, so the captain was on the hook.

The captain was brief: ‘Leha, you’re a good sailor, but don’t encourage the crew to mutiny…’.

Leha was summoned by the first mate. Spitting saliva, he hissed that the dictatorship of the proletariat had not been abolished in the USSR. On that Leha smiled and asked, “Who is the proletariat here? The idler who conducts illegal searches and writes denunciations? Or the sailor standing in front of him, working for the idler’s pocket? Leha turned and left. It was a challenge.

Leha was an experienced helmsman and kept watch with the XO. The XO’s name was Felix and he had a lot of experience on fishing trawlers in the North Atlantic. He trusted Leha to work with charts and instruments, taught him to study the sky and use a sextant. They worked in tandem, using the Loran-C system to guide the trawler to schools of fish. They drew the relief of the seabed on tracing paper, studying the fish spots and the courses to trawl along them. Thanks in large part to his XO, Leha later became a good navigator, graduated from another maritime school, again with a ‘red’ diploma.

After that incident, the first mate demanded that the officers sign his denunciation so that Leha would not be allowed to go on sea anymore. At the night watch, the XO was silent for a long time, then he said:

“Leha, I want you to know who’s who. The frond was started by sailors, but in the captain’s cabin they chickened out and set you up. They’ve shown that they’re not your friends, so why are you busting your ass for them?”

On the deck, the trawlmaster whispered to Leha that the XO had disagreed to the first mate’s demand at the meeting to have the visa closed for Leha, asking to close the visa for him too. Such a turn of scandal could have cost the first mate his career. The XO had connections in the office. And the case was closed.

On arrival at the port, the company officials were the first visitors rushed on the trawler. Ignoring the women and children who greeted their husbands and fathers returning from a long voyage, the officials were demanding an immediate report. The paperwork could wait until tomorrow, but the report was just a pretext. The real purpose of the official was to get a bribe in foreign rags before the seaman took them away to home.

The bribe was like an advance on the next voyage.

Starting with the captain, navigators, mechanics, anyone who had to do paperwork would obediently drop their share into the official’s briefcase. If a seaman failed to pay his share, the official could easily replace him with a more obedient one. The bribery system forced seafarers to risk importing junk that exceeded customs regulations.

In Las Palmas, the locals used to bring cheap alcohol and various goods to the roadstead in their boats at night and exchange them with Soviet sailors for non-ferrous metal. In the city, the sailors bought jeans, fashionable jumpers, scarves and shawls with lurex and other goods. When they arrived at their home port, all this junk was bought in bulk by gypsies. The port was a restricted area but it was no secret how the gypsies got into the area and then exported the bales of goods. The gypsies would bribe the guards at the gate. Smuggling was a business for the gypsies, and for the fishermen it was compensation for the risks of a dangerous job. The sailors hid the smuggled goods in various niches, while customs officers and border guards with dogs searched for them and often found them. The whole crew was deprived of their bonuses for the smuggled goods, which was a considerable loss. So the sailors used all their ingenuity to hide the contraband. Well, the first mate’s spies did not sleep at nights when the ship was after a foreign port on the way home. They were sniffing around. So it was the life in socialism reality, the competition of who will cheat who.

In Sevastopol, outside a special shop for seamen, Leha offered to buy from him a pair of jeans to pretty young woman. He didn’t recognize in her a popular singer, but the locals gave him a tip. The young woman turned out to be Sofia Rotaru, who lived in Yalta and sometimes visited this shop, the only one in the Crimea selling goods from overseas. The beauty was shy and just passed by. But in vain, the jeans would fit her very well. There were no such jeans in the shop!

Leha fell in love with Las Palmas the first time he saw it. For Soviet fishermen, after six months of grueling, dangerous work, a visit to Las Palmas was a visit to an earthly paradise. Approaching the islands, as soon as their mountains began to appear on the horizon, the airwaves were filled with the sounds of melodious Spanish music, non exist near the African coast of the Central and South Atlantic were they spent months in fishing. And the streets and beaches of the resort bustled with the kind of life you don’t see in the USSR.

In that visit, the XO was seconded to the local firm, to place an order for a fresh food delivery. That firm consisted entirely of Soviet KGB agents. The XO took Leha with him. Having finished their business they stopped at a harbor tavern. There the sea fraternity was buzzing and they ordered a drink. An old man approached them. He heard their speech and spoke to them in broken, but quite decent Russian. It turned out that his older brother was in Russia when the civil war was burning in Spain, lived there for years and returned home and taught his brother Russian. The offered glass of rum was gratefully accepted by the old man and he told them the story.

“Once upon a time, the Canary Islands belonged to Castile,” the old man took a sip from his glass and licked his lips, “The Portugal was at odds with Castile, and there was a rivalry between them over the ocean. In those days the Spaniards were looking for a way to the Spice Islands. These islands were somewhere in the Indian Ocean, and Columbus and Magellan both started their journeys from here, from our Canary Islands. And their ships returned with gold and precious stones, the treasures of the New World. In Spain they were obliged to share their cargo with the king, but who wants to give away their booty for free? The seafarers buried their gold in our mountains, hoping to return. But few got the chance. Where there’s gold, there’s robbers, you know..” the old man smiled.

“In 1553, French pirates plundered Colombia and Cuba, and on their way home they attacked Las Palmas, where we drink rum now,” the old man quacked. “They were led by a pirate called ‘Tumba’, who had a wooden leg. They got lucky here, captured a rich ship in the harbor and looted our little town. The brigands were aggressive and drunk, taking gold from the local rich. Those who could hid their treasures in the mountains. The pirates tortured them and many had died. And the hidden gold remained in the ground, over there”, he pointed to the blue peaks of the mountains…”.

It was sun down, when the boat was taking them to the roadstead. The stars were lighting up in the sky and the breeze, tearing the salty foam off the waves, threw it into their heated faces.

At that night Leha had colored dreams in which parrots screamed. Probably their cries made his head heavy in the morning. He remembered the old man’s story in the tavern and thought wistfully that all the sailors are forced laborers, but the pirates had been free and some of them had even gained immortality. The same pirate Le Clerc nicknamed ‘Tumba’ was immortalized by Robert Stevenson as John Silver in his novel ‘Treasure Island’. But today, nobody will remember Leha Chuguev, the fourth mate of the fishing trawler, to bring him a bottle of cold beer in these difficult moment…

Beyond Gibraltar they found the Mediterranean and familiar places. It was early spring, and the Aegean islands smelled of myrtle and pine needles. There is nothing like it anywhere else. In the Bosporus, the first mate and his snitches were busy making sure that no one jumped overboard, that no one escaped. First mate hid under a dinghy, furtively clicking his camera, taking pictures of NATO warships, preparing proof of his dogged loyalty to the KGB.

Beyond the Bosporus was the sea, the bluest in the world. But for Leha it was black. For there, on the shores of home port Odessa, they were expected by the border guards with their dogs. There was the motherland – the stepmother. Of which he had already had tired enough….

© Copyright: Walter Maria, 2024

Certificate of publication #224010100854

End of the first part.

Outstanding feature