From the author.

When Hitler learned of Stalin’s plans to invade Europe in the summer of 1941, he ordered his General Staff to draw up the Barbarossa plan and personally worked out the details. He waited patiently for Stalin to concentrate all his invasion armies on the new border they shared in divided Poland. Hitler planned to get ahead of the Kremlin pariah and launch a preemptive strike against his armies at the very last moment.

As early as 1924, the aspiring politician Adolf Hitler realized the threat that the Comintern (Communist International in Russia) posed to Europe. He made a public statement about this threat at the Beer Putsch trial, where he was charged with attempting to change the country’s political course: “What kind of criminal am I when my life is aimed at restoring Germany’s honor and dignity in the world? I want to destroy Marxism and I intend to succeed. The man destined to lead the people has no right to say, “If you want me, I will come. No, he must come himself!”

Hitler told the court that the failure of the putsch meant nothing and that Nazism was the future of Germany. He expressed his firm belief that the army would support him: “The hour will come when the masses who today stand in the streets under banners with swastikas will unite with those who shot at them… The hour will come when the army will be on our side – officers and soldiers alike…“. With the Iron Cross on his lapel, a front-line soldier he smiled at the audience. His speech impressed the entire court, even the chief prosecutor. Sentenced to 5 years in prison he got out after 9 months.

The invasion of Stalinist Russia in 1941 was aimed at overthrowing the Bolshevik regime, so Wehrmacht troops were ordered not to take Communists prisoner. Historians, fulfilling the orders of their masters, distorted all the events of the Second World War, presenting it not as a liberating, but as an invading war, ‘forgetting’ to tell about the millions of Russians who fought alongside the Germans against the communist regime (among them were 2 million Red Army soldiers who surrendered in the first months of the war). Historians have diluted their tales with many atrocities allegedly committed by the Germans in that war, but again ‘forgot’ to tell about the partisan units created by Stalin’s NKVD, which under the guise of Germans, using their uniforms committed sabotage atrocities against their population. And then the Kremlin press wrote about these ‘atrocities of the enemy’ to awaken hatred among the peoples of the fooled empire. Here it is appropriate to mention the little-known fact that the International Nuremberg Tribunal recognized the actions of the Wehrmacht following the rules of war accepted by the Geneva Convention.

Maybe readers will also be interested to learn about that war from the Germans themselves. How did they perceive their former allies, the ‘Russische zoldatten,’ and what did they learn about Russia during their time there?

The famous saboteur Otto Skorzeny writes about this in his memoirs. In the early years of the war, he was not yet what the British press called ‘the most dangerous man in Europe’. As a junior officer in a special motorized division, Skorzeny marched across Europe, and in early June his division found itself on the border of Stalin’s Russia, in Poland.

Early in the morning of 22 June 1941, the division crossed the Bug River with the advancing units and… But let Skorzeny himself tell us what happened.

FROM WEST TO EAST.

Austrian Otto Skorzeny entered the University of Vienna in 1926 and graduated five years later with a degree in mechanical engineering. He was a member of the Academic Legion and had fought 15 student duels. In one of these duels, a fighter’s sword cut deeply into his left cheek, but Skorzeny ended the duel by stabbing his opponent three times, almost killing him.

He loved motorsports and won gold medals in racing. He also enjoyed small arms shooting and sailing and had a collection of sports awards.

In the 1930s, four Saxon car companies joined together to form a company whose emblem was the four rings. These companies were Horch, Audi, DKV, and Wanderer. Later, only Audi remained in the group and Horch switched to the production of Mercedes-Benz cars.

After graduating from university, Skorzeny worked for a time in the group’s design department, and his professional knowledge of cars and motorcycles, as well as his racing skills, helped him many times during the war.

In 1933, Hitler came to power in Germany. Skorzeny took part in the Nazi coup in Vienna and joined the 89th SS-Standartement. On the eve of 1940, after two months of training, he was drafted into the elite Waffen-SS, a motorized division preparing for war in Europe. Skorzeny was a sergeant in the engineering section of the artillery division, responsible for the technical condition of the motor pool. The whole military campaign in the west seemed to him a tedious walk, with endless columns of French, Belgian, and English prisoners of war.

The SS offensive troops were the elite of the Reich, in which discipline, patriotism, and disregard for life were carried out to the point of fanaticism. Before the invasion of France, troops were given orders that the slightest misbehavior against civilians would be punished. Several soldiers of the division were severely punished for accepting neckerchiefs from French residents. At the end of the fighting in the west, the German command authorized the opening of a French brothel in Biarritz. Among the prostitutes were mulattoes. Two young SS men caught with these mulattoes were sentenced by a military tribunal to long prison terms for breach of racial discipline. One Frenchman filed a complaint against a soldier, accusing him of attempting to rape his wife. The woman showed no evidence of violence, but the soldier was tried and shot for compromising his army.

According to the memories of old Europeans, the relationship between the German army and the people of the countries it occupied was without any antipathy. Europe tolerated the German occupation as Germany’s answer to France and Britain’s declaration of war on it. There was no hatred; the people of Europe were used to living by the same principles.

Skorzeny will write in his diaries of a very different war the Germans faced in Russia. When discussing acts of mutual brutality, he would point out that the USSR had not signed the most important clauses of the Geneva Convention on methods of warfare, which provoked hatred on both sides. At the end of the Western Campaign, everyone in his division hoped for a quick end to the war. But the sad fact was that orders were received to move southeast into Yugoslavia and Greece.

It was during this campaign that Skorzeny was promoted to first lieutenant. In early April 1941, the army of thirty-three divisions, including the division that would later be called “The Reich”, crossed Hungary and Romania and invaded Serbia. The Balkans had no roads like the European highways and serious vehicle breakdowns began. Although the Germans defeated Yugoslavia in a week, the Balkan campaign pushed back the deadline by a full month, which many military commanders felt proved fatal to Operation ‘Barbarossa’.

In June, the division was transferred to Poland and sheltered in the woods near the border town of Lodz. Ahead was the Bug River, and on the right bank, the artillerymen’s optics were detecting masses of Red Army troops.

As a non-aggression pact had only recently been signed with Soviet Russia, no one believed in going to war with them. There were rumors that the Russians would give the German army free passage to Iran, with its oil reserves. Or that they would help establish a bridgehead to attack Egypt, where the British Middle East Group was stationed. But soon the orders went out to the army and it became clear to everyone that Russia itself was the target.

DRANG NACH OSTEN.

“Never plot anything against Russia, for to every one of your cunnings she will respond with her unpredictable stupidity.” Chancellor von Bismarck.

At 5 a.m. on 22 June, German troops consisting of 180 divisions, 3,350 tanks, and 7,200 guns, supported by 2,000 aircraft from three air fleets, launched a massive offensive, forming a front line from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea.

The division in which Skorzeny fought crossed the Bug River on a pontoon bridge and entered Brest-Litovsk following the advancing Wehrmacht units. There were pockets of resistance all over the city, and the Russian soldiers barricaded in casemates, fought to the last cartridge and man, refusing all offers to surrender. The Germans were surprised at the fanatical tenacity of the Russians and found that they faced a real enemy they had not faced before.

The German offensive divisions were advancing rapidly eastwards, outpacing rear units, supply, and ammunition wagons. There were skirmishes with scattered groups of Russian troops, and then came the Pripyat swamps, which swallowed up more than a thousand pieces of equipment. The Germans moved north and south in search of bypass roads, but Russian partisans and snipers were waiting for them, forcing the enemy to move under cover of darkness.

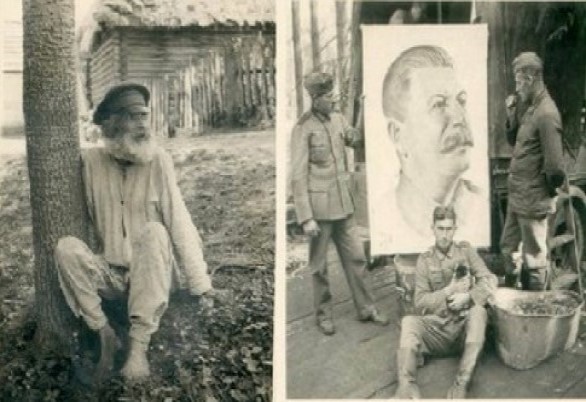

North of Koblin, Skorzeny saw with his own eyes a Soviet collective farm. Its inhabitants hid their belongings and meager food supplies in the forest, waiting for the outsiders to leave. In their dilapidated huts, the Germans found a jar of sunflower oil, several boxes of nails, a hundred dirty winter overalls, and tobacco, very strong tobacco. The peasants rolled it in scraps of old newspapers and smoked it with obvious pleasure. They ate cabbage and potatoes, sugar and butter were rare for them, and some still lived in dugouts. Time seemed to have stopped for them in the nineteenth century. There were also completely abandoned villages whose inhabitants had been driven east by the Soviet NKVD.

In a firefight with scattered Red Army units, the division crossed the Dnieper River near the town of Shklov and moved towards the railway junction of Yelnya near Smolensk. In the captured Yelnya the Germans found a large stock of Russian vodka and, having tasted the potion, were pleasantly surprised by the fact that vodka is much more effective in raising morale than schnapps. One glass made them so aggressive that they wanted to punch someone in the face.

Soon the radio announced that Stalin ordered his Marshal Timoshenko to knock out of Yeln and destroy the ‘Hitler’s dogs’, to whom he had sworn the previous day in eternal friendship. The Russian artillery fire became more and more intense, and one day the division’s artillerymen became acquainted with a new type of Russian tank, the “T-34”. It was a powerful fighting machine, against which the German guns were powerless. In one of the attacks these tanks broke through to the firing position of an artillery battery and were stopped only by the fanaticism of the SS men who attacked the enemy tanks with Molotov cocktails, magnetic mines, and hand grenades. Three tanks still managed to break out and the Germans suffered casualties.

(Reference: tank “Christie”, also amphibious tank – the name of American tanks designed by John Christie and manufactured in the USSR based on prototypes. The Russians purchased several M1931/M1928 and used them in the development of the BT-2, BT-5, BT-7, and T-34).

The Russians never picked up their wounded, each soldier was responsible for himself, and the bodies of the dead and wounded were used as cover for the next attack. The division field hospital and cemetery were at the edge of the forest. As the heights changed hands, the Russians destroyed the graves of dead Germans with incomprehensible cruelty with the tracks of their tanks.

They fought, recognized their enemy, and learned much from him. One day, Skorzeny’s assistants selected six mechanics from the prisoners to join his team. The ingenuity of these mechanics surprised the Germans. The most vulnerable part of the German car was the suspension, whose springs could not withstand Russian off-road conditions. The captured Russian mechanics used springs from “T-34” tanks, which proved so durable that they never had to be replaced. The most inventive of these repairmen was a red-haired, short man called Ivan.

“…One day I couldn’t find him and asked a corporal where he was..,” Skorzeny recalls. “Embarrassed, he replied that he had allowed Ivan to leave for a day to visit his family in a neighboring village. I was amazed at the corporal’s stupidity and scolded him for letting go of the best mechanic who would never return. Imagine my surprise the next day when I saw Ivan picking under the car as if nothing had happened. As I could find no other explanation, I decided that these Russians were happy to work for us and receive a full soldier’s ration, including cigarettes, chocolate, and schnapps…”.

A week later the division advanced to Roslavl, where Skorzeny received his first award, the Iron Cross 2nd Class, for risking a clash with Russian units by driving 70 kilometers to bring stragglers and supplies from the rear to his division. During this adventure, he contracted dysentery, which he cured in a few days with double doses of castor oil mixed with strong medicine.

The division received a new order: to advance 400 kilometers south and help close the ring of encirclement in which several Russian armies east of Kyiv had fallen.

On the march, the division’s soldiers witnessed air operations. The effect of a “Stuka” dive bomber (Junkers JU-87) dropping bombs with a wild howl on the heads of the Russians completely demoralized them.

Fifty Russian divisions were surrounded and 665,000 soldiers were captured, the largest number of prisoners in a single operation in the history of warfare. Convoys of prisoners were led westwards, and as the last of them disappeared into the dust over the horizon, the division turned back towards Roslavl. It was late September and the autumn rains had already turned Russian roads into impassable mud, with lorries stuck up to their cabs. Night frosts had turned the mud to cement, and the next day the trucks were helpless to rescue the stranded equipment.

From Roslavl the division moved on to Moscow. The road from Yukhnov to Gzhatsk passed through the woods where the remnants of the defeated Red Army troops were attacking the Germans. Near Vyazma, several other Russian armies were surrounded. A military convoy led five hundred or more prisoners, submissive, doomed, and ready for anything. When ordered to stop for a rest, they fell to the ground. Not one of them tried to escape. For the Kremlin, they were already traitors; in Russia, execution or exile in Siberia awaited them. Their faces showed nothing but apathy. For them, the war was over.

In mid-October, the town of Russa was taken. Russian artillery fired on the Germans with “Katyusha” guns, which the Russians themselves called ‘Stalin’s organs’. These self-propelled guns were stolen copies of German “Nebelwerfer” rocket launchers. However, the Russians mounted them on their light lorries, and the Katyushas were more mobile, which made it more difficult to direct artillery fire at them. Snow sprinkled from the black sky during the night and the Russian winter began.

Soon the division occupied Mozhaisk, the last line of Russian defense. It was the fifth month of the war on the Eastern Front, 1,000 kilometers deep into Russia. The soldiers’ uniforms were worn out, white with sweat and black with dirt, many had stopped shaving and grow beards. Their equipment looked no better. The tankers of the 5th Panzer Division, who had fought in North Africa, derisively called their comrades in arms ‘a bunch of beggars’, and they have immediately dubbed ‘fleas of the desert’.

One day in November, Skorzeny came under “Katyusha” fire, was wounded, and covered with mud. He was found with his arm sticking out of the ground, pulled out, and brought to his senses with vodka.

The optimism of the German army was still high: the industrial districts of the Urals were in the range of the Luftwaffe aircraft, the troops had occupied Istra and were approaching Moscow 15 kilometers from its outskirts, transport Junkers were bringing food and ammunition to the soldiers.

Skorzeny’s unit was ordered to prepare special teams to capture the water tanks of the Russian capital. Cheerful songs such as “All bad things will soon be over, and December will one day be followed by May” came from the loudspeakers.

But – 30C frost set in, lots of snow fell, equipment froze to the ground, the oil in the engines disintegrated, batteries died and the Germans’ optimism began to fade. Pessimism was added by the news of the outbreak of war with America. The war went from being a European war to a world war. In early December the Russian units began to be replenished with fresh, well-equipped, and trained Siberian divisions.

The losses of the division in which Skorzeny fought mounted, with frostbite killing more soldiers than enemy shells. Napoleon’s grim tale was becoming a reality. The Russian winter was winning! Skorzeny’s gall bladder pain worsened and he was temporarily saved by injections, but he ended up in hospital, ordered to the rear for an operation. He was sent to his hometown of Vienna.

It took several days to get to the border, a train full of wounded, with partisans everywhere. Finally, in Poland, they were given warm food and hot ersatz coffee, and the train moved faster. Skortzeny stood by the open window of the train and smoked. A sad thought occurred to him: “God is with us, he thought, was the inscription on the buckles of our soldiers’ belts. We believed that. But in Russia, God has turned his back on us…”. He drove away his depression by consoling himself with the fact that German divisions were at the gates of Moscow. His war on the Eastern Front was over.

***

COMMENT.

Hitler’s fatal flaw was vanity. He alone decided on matters of state policy and demanded that his orders be carried out without consulting anyone. This caused resentment among army commanders, which eventually led to a conspiracy, an attempt on his life, and further repression that destroyed many talented officers of the highest rank.

Hitler did not push Japan to open a second front in the East against Stalin; having defeated the main elements of the Red Army, he was confident that he would finish the job himself.

Among the journalists accredited to Japan was Richard Sorge, a spy working for Stalin. From him Stalin received information that war in the East did not threaten him, the Japanese would not attack. This made it possible to remove 40 divisions from the border and transfer them to Moscow.

Hitler’s vanity and misunderstanding of Japan’s imperial interests meant that Japan drew America into the war and the European war became a world war. Hitler was forced to move some Wehrmacht divisions and Luftwaffe squadrons from the Eastern Front to the Mediterranean. And the capture of Moscow did not take place, the German divisions moved south. After occupying Ukraine and Crimea in 1942, the Germans were moving towards the oil fields of the Caspian Sea when something happened that completely changed the course of the war…

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.