From the Author.

There are many mysteries in the history of World War II. Among them is one involving a secret mission by the Führer’s closest associate. The mission was unsuccessful and provoked a reaction from Hitler in which his impulsive nature showed itself to such an extent that it is worth telling. Scholars from many countries continue to break spears around that mission, which ended in life imprisonment for the perpetrator. During my research, I discovered information that sheds light on that story…

***

In the spring of 1941, a two-front war was becoming inevitable for Germany. Hess, the Führer’s closest associate, tried to persuade him to negotiate diplomatically with the British. Seeing Hitler’s efforts fail, Hess made a desperate attempt to do it himself, in secret from everyone.

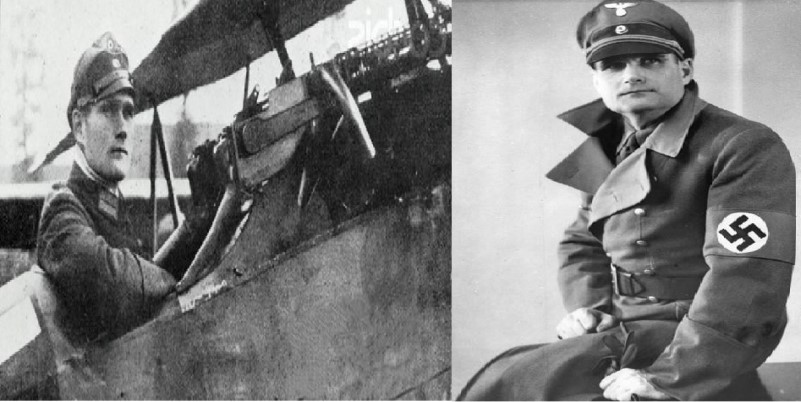

Rudolf Hess, a World War I military pilot in the Third Reich, was the second man in the hierarchy after Hitler. He continued to fly, already as a test pilot for Messerschmitt, whose owner, Willy Messerschmitt, was his friend.

At 17:45 on 10 May 1941, wearing the uniform of a Luftwaffe captain, Hess took off in his ME-110 long-range fighter and flew to England. At night, having reached his destination, he parachuted out of the plane and landed in a field. Awakened by the explosion of the plane, the farmer ran out of the house and saw a man in a German uniform who introduced himself as Captain Alfred Horn and asked him in good English if Duke Hamilton’s estate was there. The farmer replied that the castle was 12 miles away and called the local air defense headquarters. The stranger did not resist the arrived military and asked to see the Duke to whom he had important information.

The strange visitor was reported to the Lord Steward of the Royal Court and around 10 am Duke Hamilton arrived at the police station. “We met at the 1936 Olympics,” the visitor said when they were alone, “I am Rudolf Hess.” The startled Duke immediately telephoned Prime Minister Churchill. He ordered that Hess be kept in complete isolation and that as much valuable information as possible be extracted from him.

Why did Hess make this mad flight in the heat of the war between the two countries, and what was his mission? Was Hess sent by Hitler?

Hess had conversations with important personalities but did not face their support, and his mission failed. What was the secret that led the official authorities to classify the documents relating to this visit of the Nazi leader to England? This secret was kept for a time, unprecedented in history.

Hitler hearing of the escape, rejected Hess, his closest friend and comrade-in-arms, and declared him insane. According to the official German version, which was broadcast over two days at 8 pm on 12 May 1941, “…Hess has gone mad from hard work…“. Hess was replaced as Reichsführer by Martin Bormann.

Hitler’s associate Rudolf Hess went into hiding in Austria after the Beer Putsch of 1924. After learning that Hitler had been convicted and imprisoned, Hess returned to Germany, surrendered to the authorities, and asked to serve his sentence with Hitler. Hess was a graduate of the University of Munich and had extensive knowledge of sociology and economics. The two wrote Mein Kampf together, with the erudite Hess editing and polishing Hitler’s emotional phrases. Paper, pencils, and ink were sent to them by Winifred Wagner, the wife of the famous composer’s son, a great admirer of Hitler. They were given a typewriter by the warden, who shared the prisoners’ views. Hess was Hitler’s favorite.

In 1933, Hess was appointed Deputy Führer and Reich Minister without Portfolio. In 1939 he was appointed a member of the Reich Ministerial Council for Defense Policy. He never tried to replace Hitler, deeply respected the Führer, and obeyed him completely. They wrote the book “Mein Kampf” together in prison. And now the second man in the Reich decides to go mad and flies to the country Germany is at war with. And his closest friend, who called him “my Rudy”, calls Hess crazy and threatens to shoot him if he returns… Why did Hess’s actions infuriate Hitler?

Hess was held in the Tower until the end of the war, becoming the last prisoner in the history of the ancient fortress. On 6 October 1945, Hess was taken to Nuremberg. An international tribunal sentenced him to life imprisonment, not death because he had not participated in the grave crimes of Nazism committed after his escape.

At the trial, Hess tried to reveal the secret of his mission in his closing statement but was interrupted by the British prosecutor. Hess’s last words in court were “I regret nothing”. He never spoke again. Hess spent a total of 46 years behind bars and died in mysterious circumstances on 17 August 1987. He had been the only prisoner in Berlin’s Spandau prison since 1966. After his death, the empty prison was bulldozed to make way for a shopping center.

His son Wolf-Rüdiger suspected that the British, fearing exposure, had poisoned his father. On 20 July 2011, the German authorities exhumed Hess’s remains and scattered his ashes because his grave in the Wundiesel cemetery had become a place of pilgrimage for neo-Nazis. Judging by the 18,000 pages of material declassified by 2017, the British did not learn anything of particular value from Hess. But why didn’t they declassify the rest of the documents but hide them until 2040?

On this, one of the most mysterious secrets of the war, there are opinions from officials of the time. Kim Philby, a Soviet intelligence agent, a British intelligence agent, and a Gestapo agent copied some of Hess’s interrogation reports and sent them to Stalin. He did not fully trust the information he received and suspected that the British had managed to hide something important. “The Hess incident has undoubtedly intrigued the Soviet Government like nothing else and may revive their old fears of a peace settlement at their expense,” reported British Ambassador Stafford Cripps in London.

Post-war researchers are still racking their brains to unravel the mystery. Here are some plausible versions to explain Hess’s mad act:

Version One.

The British researcher John Costello, in his 1991 book “The Secret History of the Hess Peace Initiative and British Attempts to Deal with Hitler”, argued from circumstantial evidence and inference that there was a powerful group within the British elite willing to make peace on Berlin’s terms. Hess flew to meet its members.

Having worked out the details and secured high-level German guarantees, they were to go to King George VI and persuade him to replace Churchill with Lord Halifax by an act of will. As a result of these behind-the-scenes maneuvers, peace with the Reich would be signed. However, it was thought that such a move could cause a political crisis in the kingdom and an early general election. The betting was that even after such a scandal, it was unlikely that most voters would consciously vote to continue the war.

Version two.

Statement by Allen Dulles, head of the Office of Strategic Services in Bern during World War II, the future director of the CIA. In 1948, Dulles stated: “British Intelligence in Berlin contacted Rudolf Hess. He was told that if Germany declared war on the Soviets, England would cease hostilities.

Version three.

The Russian historian Herman Rozanov, in his book Hitler and Stalin, claimed that Hess carried out the Führer’s orders. All the details were supposedly worked out during a five-hour meeting on 5 May 1941, during which Hitler warned his comrade-in-arms that he would disown him if he failed, and the old friends supposedly parted with tears in their eyes.

Version four.

In his memoirs, Nikita Khrushchev quoted Stalin: “…Hitler gave Hess a secret mission – to discuss with the British the possibility of ending the war in the West, to free his hands for an attack in the East…”.

MY FINDINGS.

About the conversation between Hitler and Hess on the eve of the flight and Hitler’s reaction immediately after the flight only one officer from the Führer’s entourage knew. He was the Führer’s adjutant, SS Major Heinz Linge. Unlike those who speculated and surmised, Linge was an eyewitness, that is, he was present at the meeting of two comrades-in-arms, saw with his own eyes, and heard with his ears what he told about in his memoirs many years later.

His memoirs were inaccessible to many post-war researchers as they were not published until 1980. Linge wanted his memoirs published after his death. I have a book of his memoirs in my home library, and among the many unknown facts in them is evidence that sheds light on one of the most mysterious secrets of that war.

SS Major Heinz Linge (in photo in black uniform) served as Hitler’s valet and bodyguard from the first days of the Führer’s rise to power until his last day in the bunker. In his memoirs, he claimed that only Eva Braun was closer to the Führer. Lynge was obliged to attend all of his chief’s meetings and almost all of his confidential receptions. His testimony is credible. Here are excerpts from them:

“…Rudolf Hess was distinguished by his accessibility. Anyone could talk to him, even argue with him. He listened carefully to the other side’s arguments and presented his own politely. Unlike Bormann, he was not a vindictive schemer, he was honest and courteous. He had his quirks, such as a strange diet or a passion for astrology. He always told jokes with a serious expression on his face, leaving the person he was talking to lost, unsure whether to smile at the joke or stand there with arms outstretched.

In common parlance, Hess was not normal. In the heat of a meeting, he could lift a chair over his head and stretch his stiff legs. He was not embarrassed by the presence of such Party members as Goebbels, Goering, Bormann, and Himmler. But he would never allow it in the presence of Hitler. He was not mad, we all loved him. His escape to England on the night of 11 May 1941 shocked us all…”

“At 9.30 that morning, Karl-Heinz Pinch, Hess’s adjutant, and Albert, Martin Bormann’s brother, came in excitedly and asked to wake the Führer on an urgent matter, adding that they had delivered Hess’s letter to him. That night Hitler did not go to bed for a long time and asked not to be disturbed until noon. So I refused to let them in. Then Pinch exhaled: “… Hess left Germany by plane…!”.

I felt the ground slip out from under my feet. When I knocked on the Fuhrer’s bedroom door, he answered immediately and asked what was wrong. No sooner had I mumbled the news in a trembling voice than the door opened and Hitler appeared in full uniform, clean-shaven. He had been expecting something, and I could find no other explanation for him being in full uniform at 9.30 in the morning, when the day before he had ordered me not to disturb his sleep until noon.

Pinch gave him Hess’s letter, and Hitler’s first question was whether Pinch knew its contents. When he replied in the affirmative, Hitler summoned the bodyguard and ordered his arrest: “…I have ordered your arrest, not because you knew what Hess had written in his letter, but because you did not report it to me immediately. Who is the Führer – me or Hess?” he asked.

Pinch swore allegiance to the Führer and justified himself by saying that he had only followed official security orders in opening the letter. Nevertheless, he was sent to a concentration camp…”.

“…Hitler was furious, everyone tried to stay away from him that day. I could not hide because of my official duties, and I was close by and saw and heard everything that happened before my eyes. I noticed that Hitler showed his emotions only in the presence of others. Something in his behavior suggested to me that the Führer not only knew of Hess’s mission but perhaps risked sending him as a mediator, using his last chance to try to reach an agreement with England. Hitler summoned Bormann and Ribbentrop. Their discussion took place behind closed doors and led to Hitler’s official statement two days later. In it, Hitler described Hess as a sick man who had brought Reich policy to the brink of disaster with his crazy idea.

Bormann replaced Hess in the Führer’s entourage, and it was the schemer’s dream. But Hitler, knowing Bormann, kept him at a distance. Unlike Hess, whom Hitler regarded as an equal, Bormann was a servant and Hitler treated him accordingly.

The failure of Hess’s mission infuriated Hitler. But I’m sure the mission was not a surprise to the Führer. A few days before the flight, the two Parteigenosses had a conversation that lasted about four hours, something that had not happened between them since the first day of the war in September 1939…”.

COMMENT.

The Führer’s adjutant confirmed that the two had spoken.

With the plan to attack Russia past the point of no return and an attack imminent as early as the following month, Hess decided to make a desperate attempt. He did not dissuade Hitler from attacking Russia, but he offered to use his connections with the British aristocracy to try to get Britain out of the war after an attack on the USSR. He reminded the Führer of the promise he had made to the nation in the pages of their common book, never to fight on two fronts. It was the two-front war that led the country to defeat in the First World War.

Hitler replied that he had no choice and that only a blitzkrieg in the East could save the situation.

In this conversation, Hitler proved to Hess that his years of diplomatic efforts since 1933 to achieve peace and understanding with Britain and France had come to nothing, and he believed that another attempt by one man alone would inevitably meet the same fate. But Hess was obsessed with saving Germany and took a mad risk.

Hitler knew more than anyone else about Hess’s expansive character and unpredictability. For this reason, Hess was never present at any of the Führer’s important diplomatic negotiations. For the same reason, Hitler banned the emotional Hess from flying for a year.

Hitler was furious that Hess had disobeyed his orders. He feared that Hess might inadvertently reveal the date of the invasion of Russia. After all, if the British had known the date of the attack, Stalin would have known immediately. And he would have rushed to attack Germany, wrecking all the blitzkrieg plans.

The Führer did not fully know his favorite. Hess was an officer and understood what a state secret was. When he offered the British a military alliance, he did not give them a date for the invasion of Russia by German troops. Hess’s mission was to try to negotiate with the British to avoid a war on two fronts and to secure the rear, before marching east. The failure of his mission was fatal to the Blitzkrieg in Russia.

© Copyright: Walter Maria, 2019 Certificate of publication #219110700796

Be First to Comment